The world’s most beautiful railway ticket

Thanks for all the positive comments on last week’s essay, “The Camel’s Ass”—yet several of you responded by saying, “Right, that’s it. I’m never going to Egypt. Thanks for warning me.”

I should have made my point clearer: it was only at the tourist sites that I found touts and hucksters like Hassan and the camel/perfume shop owner, sensing money like a shark smelling blood in the water. Everywhere else in Egypt I was met with kindness, good humor and hospitality.

To set the record straight, here are two other stories from the same trip.

I arrived back from Alexandria at Ramses Station after dark, hoisted my two packs onto my shoulders, forged out onto the crowded platform, and guessed my way through a side-exit to the drop-off-and-taxi enclosure which was, of course, mayhem. Two taxi touts each wanted 40 pounds for the journey to my hotel in Zamalek, and I turned them down without a shred of conscience. Once I was away from the train station, I was pretty sure, the taxi fares would drop by half. Doing my best to remember the layout of Cairo in general and the downtown area in particular, I strode out into Ramses Square.

The night was hot, humid and alive. Even though it was nearly 9:30, the square was as crowded, possibly more so, than it had been during the day. Hawkers had laid out blankets or tables and were flogging shoes and sunglasses. Minibuses were pulled up here and there, with one young Egyptian yelling the destination over and over and others crowding around or waiting in clusters of twenty or thirty on the sidewalk, lapping over into the road. Scores, maybe hundreds of others crossed the square, wandered in and out of the lighted shops, all of which were open, headed down into the underpass or up the steps to the flyover. This was Cairo at night, at ground level. The darkness seemed to glow.

At once I lost my tiredness, my apprehensiveness, even the weird chest/sinus infection symptoms I’d started to call Mid-Nile Virus. This was more exhilarating than anything else I’d seen since I arrived. Working through the crowd, I found a road heading in what I reckoned was the right direction, but it turned out to be a minibus-only loop; I hadn’t realized that the entire square was, in effect, a bus station. I flagged a taxi and asked if he’d go to Zamalek. He scowled and shook his head. The next road was heading the wrong way. The next was another minibus loop, the sidewalks becoming, if anything, even more crowded and alive. I had thought that Alexandria was the epitome of bustle, but this was the capital of bustle, the Mecca of bustle.

By now I was on the opposite side of the square from the railway station, and at last I saw a taxi skewed over by a sidewalk. I waved. He waved back. “Zamalek?” He nodded.

I got in, taking the financial bull by the horns. “Twenty pounds,” I said.

“Five twenty,” he said.

Well, I thought, it is night, and getting a cab apparently is going to be a harder job than I thought, so I agreed. I piled into the absurdly cramped space behind him, he waved me across to the other seat, I disentangled myself from my own feet, and we were off.

Within seconds it was clear that this was no ordinary Cairo taxi driver. This was the Ramses of taxi drivers. He had refitted his horn with an echo control so that by touching it once he could produce a torrent of fifteen or twenty diminishing honks, and he headed into the massed traffic as if this neat piece of automotive technology gave him the power of a sonic icebreaker.

The first road he tried was simply wedged shut with cars and taxis, so he turned into an alley—not a dark alley: everything in downtown Cairo was alight with shop window displays and car headlights—and shot at twenty or thirty miles an hour between rows of parked cars into gaps full of pedestrians with the unconcerned concentration of a racing driver punished by being sent back to Driver’s Ed and taking the cone slalom at the speed of sound.

The short cut took us to another main shopping street that was as solid with traffic and as overrun with people, young and old, as the one we had left, possibly more so. Ramses was delighted, though: right in front was a taxi-driver mate of his, whom I’ll call Khufu.

Khufu had clearly not seen Ramses since Ramses had installed his Jimi Hendrix Model II Taxi Horn, and Ramses was only to glad to demonstrate. He did the fast multiple echo. He turned the echo rate down and demonstrated again. He did the single blast, no echo. He was just about to move on to the fuzzbox echo and the wah-wah echo when the traffic at last shunted forward a little, and Ramses was making gaps where none existed, getting quarts of traffic into pint roads, all the while calling to Khufu and demonstrating his horn.

In the front seat of Khufu’s cab sat a young lady in a black burka, her pale face glowing in the fluorescent shop lights, staring straight ahead as if trying to pretend than none of this was happening around her, looking for all the world like a nun at a pro wrestling bout.

In the middle of this traffic, by the way, was something I’d never seen before, and a genuine Cairo sight: a battered BMW.

Cars began to move a little, and Ramses continued carrying out traffic surgery, apparently paying little or no attention to the cars around him or the pedestrians stepping off the sidewalks like extras on Frogger. Instead, he maneuvered so as to be next to Khufu and for the next two or three miles, utterly improbably, we kept going side by side, Ramses calling a running series of jokes punctuated by effects on his horn, Khufu laughing and calling back, the nun unmoved, unamused. At one point Khufu leaned over and threw a cigarette from his car to Ramses, who juggled it, grinned, waved, honked, and lit up, all while driving.

We reached a large traffic circle, again completely locked down with traffic. It was now about ten o’clock: rush hour. Roads and sidewalks alike were impenetrable with humanity. Cairo had reached its peak, its essential identity.

Ramses shot straight at the idling cars in front and inserted his front right wing just ahead of the left corner of a bus. The bus driver growled something at Ramses, who responded with some kind of good-natured insult, calling the driver “Excellence”—that is, “Your Excellency” in French. I was astounded at this display of verbal mildness. In London, in New York—well, you know.

Finally, as we reached the approaches to the flyover and the bridge, the traffic began to break up, and now Ramses revealed that he had not only extra features to his horn, but another seven gears in his gearbox. He shot up the ramp as if preparing a leap over 22 buses into Tunisia.

Years ago, I had a friend who volunteered as an ambulance driver EMT for his college Rescue squad. “I tell you, man,” he said, chuckling, “when you hit that siren and you cut through a busy intersection at fifty, hey, it’s better than any video game.”

This seemed to me a strangely self-interested reason for being in a selfless profession, but I guessed I could see what he meant. Here in Cairo, Ramses was now up on the bridge, which was bristling with late-night strollers, lovers and fishermen, racing toward Zamalek, leaving the turnoff until the last minute and downshifting into seventeenth. I had long decided that, for all his apparent insanity, he was either the world’s best urban driver or else protected by Horus, Seth, Isis, Osiris and every other figure of the Egyptian pantheon, and was sitting back in my seat loving it.

He didn’t know Charia Ismail Mohamed, so I told him (all this by sign language) that I’d direct him, so we burst into the narrow, quieter, darker streets of Zamalek at only forty or fifty with him looking over his shoulder as I indicated right and left. He took an unexpected early turn, and from then on we kept on not being able to turn left because of no-left-turns and no-entries, but I figured out how to get us back on track and he kept on not killing people.

When we screeched into a space the size of a mousetrap right in front of the Horus House Hotel, I gave him forty pounds. He was astonished. “Very. Very good,” he said. “Very, very good.”

I couldn’t have agreed more. It had been the best way to see the city, it had been a wonderful exercise in trust, and it was better than any video game.

The following morning I spent three hours mailing a parcel.

By now I’d amassed several pounds of books—books on bird flu, books on Arabic, books on Egypt, books on bird flu in Arabic, books on bird flu in Egypt, novels, novels about Egypt. As yet no novels about bird flu: clearly a niche in the market there.

I didn’t want to lug them all around England, where I was breaking my return journey, and then back to the U.S., so Dido, the presiding goddess at the Horus, found me a box (rather confusingly pronounced “books” by an Egyptian speaking English, which led to several periods of confusion, especially as they pronounce my name “Books” as well) and I packed them up with some data CD’s, a Tom Jobim CD, the tape recorder and batteries and tapes that I never used, and some spare clothing as padding. Dido gave me clear instructions to tape the box (or possibly the books) up very well, to put my name and address and phone number on the top and on the side, and I was ready to lug the thing down to the Post Office on Charia El Brasil.

The Post Office sign also featured the Giro sign, the UK service for sending money, and when I first entered, that’s what all the customers at the four windows were apparently doing. Money was changing hands, being counted (the elderly customer next to me even seemed to be giving a little back as a tip, which startled me) but not a letter was in sight. Had I come to the wrong place? Was Egypt Post a branch of Arabic Math, well beyond mere letters and so far into the Information Age that it transmitted only money and data, and preferably not even data? Come to think of it, this may not be solely an Egyptian phenomenon. After all, Western Union started out sending telegrams but now pretty much only sends money.

Soon enough a window cleared and a middle-aged woman clerk in headscarf turned her attention to me. I had my box, which was about the size of a case of whisky, on the counter, and as it wouldn’t fit through the little half-moon window, she beckoned me to go out the front door, around the side and in through the Government Employees Only entrance, where to my surprise she kept beckoning me and gestured to the metal stool with the green plastic seat where she had been sitting.

I felt thoroughly privileged. Apparently, my presence behind the counter wasn’t that much of a stretch for the Post Office, given that nobody paid me any attention and in any case the Employees Only side door wasn’t shut, let alone locked, but even so I had that feeling of being given a backstage pass and rubbing shoulders with the giants and stars of the Egyptian postal service.

She took the box, weighed it, and in very good English explained that it could go Express, which would cost 640 Egyptian pounds.

Wow. More than $130? I cut her off and told her we’d take the slow and cheap route. Another calculation: 300 pounds. Okay, I said. I had 300 on me. She nodded—but a complication arose. The box weighed six kilos. To go by post it had to be broken down into three parcels of two kilos each.

She raised her eyebrows. Okay, I said, slightly baffled, and she went to work, digging out the crumpled pieces of paper I’d used as filler and dropping them on the floor. I made to pick some up and throw them in her small metal waste-paper basket, but she wouldn’t hear of it. “My job,” she said.

Part of the padding I’d included was a high-quality paper shopping bag from a bookstore. She put books and my tape recorder in that, and proceeded to tape the bejasus out of it. Using that thin brown plastic wrapping tape and scorning a pair of scissors, she taped every edge, then every corner, then every side, laying down tape and stabbing the end with a ballpoint pen that broke off the tape with a satisfying snap. Meanwhile, she had torn off three pieces of regular white paper and told me to write my address and phone number on each of these. I did so.

“Write `From,’” she added, pointing to the top, so I wrote the address of the Horus on each of them.

By now she was on the second parcel, folding a pair of trousers around more books and CDs and then placing them carefully in a cardboard box she had found on the floor, which she broke down until it was the right size. A thought struck her. She explained that the “From” address needed to be the Post Office rather than the hotel, so could I make another set of “From” labels saying my name, Zamalek Post Office, the postal code, Cairo, Egypt? Sure, I said.

All this time, business behind the counter was going on as usual. Five or six employees were handing money to customers, or to each other, or answering questions. The guy next to me worked on his computer, in Arabic, doing more Arabic Higher Math. Still no actual mail going on. One young man came in with three air mail envelopes, but I didn’t see the envelopes or any stamps cross the counter, and next time I looked up he had gone.

After some 25 minutes my postal friend was on parcel number three, wrapping the last few books (and my entirely unused CD set, Learn Arabic!) in brown paper and once more wrapping the paper in tape to the point where no paper was visible. She took the return address slips and taped each one to a parcel with clear tape, once more taping over every iota of paper. If these parcels didn’t reach me in the U.S., it certainly wasn’t going to be her fault. By the time she was done with it, the parcel looked like a rather battered piece of plastic fruit.

So far I’d been in the Post Office, behind the scenes, for about 40 minutes. She held the parcels up for my inspection, I nodded and gave her the thumbs up, and she passed them over to a colleague, who also looked them over. Clearing paper, tape, pen and scale to one side of her tiny desk space, she pulled the calculator toward her.

Oh, dear. The three-parcel method was going to cost more. She worked it out. Four hundred and two pounds seventy-five.

“I haven’t got that much on me,” I said.

“No problem,” she said. She gestured to the parcels, gleaming like dun-colored placentas. “You leave here. Give me three hundred, come back later.”

Later, when I looked back on Cairo in general and this little excursion in particular, I couldn’t help remembering that when I told people in the U.S. that I’d been in Egypt, at least half immediately looked concerned and asked if I’d been in danger. And when I said that the only danger came when I tried to cross the road, and that Egypt in general has a low crime rate and an almost non-existent rate of violent crime, many people assumed it was because of a harsh penal system, as if the place was swarming with police and Arabic nations cut off the hands of anyone picking a tourist’s pocket.

Fact is, I saw barely any on-the-beat police, and nobody with a missing hand. I’m not sure why the Egypt I saw was better-behaved and felt safer even than Vermont, supposedly the safest state in the Union. Part of it, I’m sure, has to do with alcohol. Egypt, like most Muslim countries, is not entirely dry, but practicing Muslims don’t drink, and the net consumption is thus much lower than in Western countries. Nor is Egypt drug-free, but drugs don’t seem to be as much of an issue as they are here: informed sources tell me that there are at least three well-known drug dealers living within a block of my house in Burlington, and when Maddy, at thirteen, is afraid to take our dog out for her evening walk, I don’t blame her.

Somehow we forget these home truths as soon as the issue of travel comes up. The so-called war on terror has managed to do what the Cold War did: distort our sense of threat. Two of my female colleagues from Champlain College also spent some time in Egypt a few weeks before me. When they came back and said they had felt entirely safe, day and night, people just didn’t believe them.

In the direct sun outside the cool interior of the Post Office, the temperature was cresting around 117 degrees. I walked back to the hotel, found another 200-pound note and went back to the Post Office. My moment of privilege was over, I judged, and went in through the customers’ door. Her face lit up. I gave her 202.75 pounds, and she gave me 100 pounds in change.

“Can I have a receipt?” I asked. My college was paying for this trip, and they (understandably) wanted receipts for absolutely everything.

Her face fell. Receipt was only for Express, she explained apologetically.

Could she just write something down on a piece of paper?

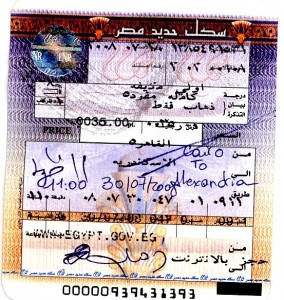

She tore a form off a pad, turned it over, and on the back wrote not just a receipt but a letter, almost a poem.

She turned it around to show me, and read, right to left, the glorious Arabic script that manages to be simultaneously ornate and joyful.

“This is the money,” she said, showing me the Arabic numerals that I now recognized. “Under is saying that for this money I am taking parcel, I am making ready and I am sending to America. For you.”

She took her official stamp, inked it, and whacked my poem-receipt.

The college was adamant: to get reimbursed, I had to turn in the original receipts, not copies. In this case, though, I was going to trust to luck and hand them a photocopy. I was keeping this one.

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post

Ahhh,what joy it was to stumble onto this page to read this!

I live in Brazil Street and I have myself watched and heard the “satisfying snap” from this womans ballpoint pen!

The “finale”gave me goose bumps!!……and hand them a photo copy.I was keeping this one.”

If it is possible to fall in love with an author because of the way he writes,then I´m in love with you Tim Brooks.

Stella.

Leave A Reply