First, the background. We go back five years.

A Barrel of Monkeys

By five o’clock the pick-up game of soccer was just getting good. Two dozen of us had straggled down to Oakledge Park around 3:30, as usual, and after ninety minutes several people had had enough, so as the sun began to sink over Lake Champlain, spaces were starting to open up. For a forward–and at 52 I play as a forward because, dammit, I want to score a few goals to replay over and over in my mind’s eye once I’m forced into retirement–there was finally room to run, to attack the goal, to play passes that knifed through the heart of the defense.

I had been longing for the game even more than usual, because the previous week–well, the previous three weeks, really–had been stressful beyond belief. In mid-August I had been appointed director of the writing program at the college where I teach. After twenty-seven years in the United States, I finally had a full-time job with benefits–but it came with two catches.

The first was that, as an indentured member of the academic fringe, I’d never had to know anything about credits or electives or pre-requisites or course numberings–I was free to just go in and teach like a man possessed. Now I had to learn everything about running a program with ten instructors and two dozen courses, and I had to learn it in a week and a half, while writing six syllabi and getting ready to teach two courses I’d never taught before.

The other catch was that I been hired for only a year, during which time the college would carry out a national search and make a permanent appointment. As the human resources officer started to walk me through my benefits package I began to see how much I had been paying out of pocket all these years, how marginal my freelance life had been. The prospect of having these benefits for only a year, and then being thrown back out on the side of the road, was ghastly. It was clear what I had to do: I had to be not only the best program director the college had ever seen, I had to be the best program director they could imagine.

No pressure, eh? I worked all day, every day until ten at night. Most of the time I felt as if my stomach was being gnawed from within by a large rodent. My chest was as rigid as a barrel, the ribs like horizontal staves. My mind was so occupied elsewhere, though, I barely noticed; and when I did, I took half a dozen deep breaths before hurrying on to the next job I didn’t know how to do. I couldn’t wait to get some fresh air and exercise.

Someone on my team played a through pass and I took off after it, but was fractionally too late: the big Russian guy playing sweeper stepped up and hoofed the ball away upfield. As I pulled up, I felt dizzy, and realized my heart was racing. I stood still for a moment, shook it off and got back into the game.

Another quick sprint, and it happened again. I slowed down and waited for it to pass. It wasn’t the first time my heart had done strange things–a sudden, extra off-beat thump, then a sickening pause, then back to business as usual–but when I’d asked a doctor about it he had listened to my heart, told me that I was perfectly healthy, dismissed it as a normal occurrence and said I should stop being such a wuss.

This time normal service was not restored. My heart was apparently playing a game of its own. Six beats in quick succession, then one of those sickening pauses, then four, then six more, then apparently none at all. I went over to the sidelines and sat down.

Whatever was going on with my heart had the odd effect of breaking up my sense of the continuity of the day, or the coherence of everything around me, into oddly-shaped fragments. It felt as if things in general, not just my heartbeats, were happening in short, stuttering rushes. I cadged some water–tried to catch my breath. People asked me what was wrong–I tried to tell them, at the same time shaking my head at the oddness of it all–someone said I should call it quits for the day–I said yes, probably I should–pulled my things together and got up, a little uncertainly–made my way over to my car. My body, too, had lost its unconsidered balance, and walking had become an act of concentration and will: it felt as if I were walking on stilts.

I didn’t think I was having a heart attack. Here and there I had somehow picked up bits and pieces about heart attacks and tucked the information away without telling anyone, even myself, what I knew. Heart attacks were painful—they felt like cramp—the muscles contracted hard—the pain sometimes went through the left shoulder, or down the left arm. As potentially life-saving information went, it wasn’t much, but it was just enough to keep panic at bay, panic being, in my view, the worst attack of all.

I drove home slowly. My car’s engine was running smoothly, for once, but my own was racing, braking, racing, braking.

It was strange to have lost my sense of rhythm, something I had taken for granted so deeply that I didn’t know I had one. There must be some kind of synchronization, in the normal state of things, between heartbeat and breathing and pretty much all physical activities. I once saw a film of red blood corpuscles moving through a capillary. Instead of flowing steadily, like a river, they shunted forward en masse, kicked by the cardiac pump, then stopped, then shunted forward again. And with that shunting motion, everything around them shook slightly. The heart was not only booting the blood around the body, it was booting the body as well, giving the whole system that reassurance that as was well, was working at the right pace for the circumstances. They say that the fetus hears the thump and whoosh of its mother’s pulse: maybe this is the deepest of the truths we know, this sense that the cardiac rhythm is running through us, that everything is sychronized and working as it should.

There’s something profound about this pervasive rhythm, something universal. That week, a study in the journal Heart showed that music with “a slow or meditative tempo” tends to slow the pulse of those who are listening to it–especially musicians, as it happens. Other research has shown that music can alleviate stress, improve athletic performance, improve movement in neurologically impaired patients with stroke or Parkinson’s disease, and even boost milk production in cattle. The rhythm of music, then, spoke to another rhythm so essential that it seemed to underwrite virtually every bodily activity. Who knew how it would affect me if that rhythm was now fragmented and lost?

When I got home I did what we English do in times of trouble: I took a bath.

I lay in the hot water and tried to relax, but it didn’t work. Instead, the bath left me alone with the strange sensations in my chest. They felt, I decided, like a barrel of monkeys. The heartbeats leaped and scurried around at whim, sometimes apparently at the base of my throat, sometimes pounding at my ribs or my sides.

I let a long breath out and let my body weight fall, and the unruly contents of my chest began to sink too. For a second, in the luxurious relaxation of the outbreath, it felt as if one of two things was about to happen. One was that my heart would settle back into its old rhythm as if life were no more than a pile of bedlinen, and all I ever had to do was relax into it. The other was that I was dying, and by letting my breath go I had let go whatever strange unconscious commands I habitually send to my heart. It would sink into silence like a shell falling through the darkness of the sea, and I would die, but that would be okay, because even dying involved recovering, in a way, from this unnatural and disturbing series of broken rhythms.

Neither happened. After an instant of warmth and calm, my heart gave a deep kick right through to my back, and burst into a reckless stampede of activity. Whatever was going on, there was clearly going to be no easy answer. The monkeys shrieked and chattered and threw things. I got back out of the bath, shaken and uneasy. All the bath had done was to demonstrate with unpleasant clarity how deeply this disturbance ran. We speak loosely of the heart as the core of our being, but it’s usually just a romantic figure of speech. For the first time I thought of my heart as something utterly central to my psyche as well as my physiology. It had run amok, and because of that everything about me was amok. We think of the heart’s rhythm as internal, but it has everything to do with how we understand the world outside us. It is, then, a wave that encompasses everything, outer and inner.

Barbara, my wife, had made dinner, but every time I stood up, I felt dizzy again, and the effort of walking to the table tired me. My appetite had vanished. It was strange: all this activity inside me, yet in general I felt sluggish and distant from myself.

By eight p.m. the monkeys had shown no sign of settling down. I called my doctor.

“I would go to the emergency room, if I were you,” he said quietly but clearly. “I would go right now.”

* * *

“Cardiac arrythmia,” I told the admitting nurse, feeling slightly giddy–not just from lack of oxygen, but giddy with importance: for once I was turning up at an emergency room with symptoms so dramatic that there was no way I could be told to take a seat and then be ignored for two hours.

Sure enough, she sat me down at once and took my blood pressure. Her eyebrows shot up, she beckoned an orderly and sent him for a wheelchair. It turned out that my blood pressure was 84/60. If it had been much lower, I’d have been in danger of passing out.

The technician laid me on a table, stuck electrodes all over my hairy chest and turned on a heart monitor. He stared at the screen, which had been turned, perhaps prudently, so I couldn’t see it, but I could imagine what it showed: instead of the familiar parallel green lines with the up-and-down jags at regular intervals it must look like scribble. And even thinking “scribble,” it struck me that handwriting, too, conveys a sense of rhythm, and that my own handwriting, in the days before this strange attack, had been even less legible and orderly than usual.

Still no pain, just that odd sense that my insides were off balance. I kept taking deep breaths, as if this would reboot the system, and sure enough as I held my breath my heart would pause, like an old friend trying to fall into step with his buddy; but as soon as I let the breath go my heart raced as though it had fallen terribly behind with its work, and needed to catch up at all costs. Another six or seven quick beats, then a hesitation like an elevator stopping, then another quick tattoo of beats.

An hour went by. Time seemed to have become lumpy and inconsistent because of my own erratic metronome. The hospital bed, too, seemed uneven and uncomfortable. I fidgeted.

With nothing else to do, my mind wandered. My father died young, at 52, from lymph cancer following some heart trouble. For years I had been aware of 52 as a shadow, a threat. Most days I was sure I’d live past 52 because I was so much fitter than he had been–exercised more, weighed less, had never smoked, ate a healthier diet—but all the same it was a landmark I wanted to pass, to leave well behind. Now, getting increasingly uncomfortable on the hospital bed, I added up years and tracked back and forth across a mental calendar. If my heart had been capable of sinking, it would have sunk: I was the same age, to the week and perhaps even to the day, that he was when he died.

Eventually a doctor came in, studied the monitor readings, took my blood pressure again, and told me that the technical term for the barrel of monkey was atrial fibrillation—A fib in medical shorthand.

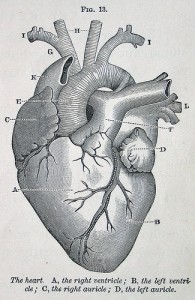

The heart, he said, is made up of four main chambers. The two lower ones, which are larger and stronger, are called ventricles. They do the hard work, pumping the blood out around the body. The two upper chambers are holding tanks: blood flows into them after its journey around the circulatory system, they fill up, a valve opens and they contract, each pouring the blood into the ventricle below it. The valve then shuts, the ventricle contracts, and the blood is on its way again. Each upper chamber is called an atrium, plural atria, adjective atrial.

Under normal circumstances, he said, all this activity is coordinated by electrical impulses in a small patch of tissue called the sino-atrial node, or SA node. (I couldn’t grasp this. Heart tissue acts as a kind of fleshy electrical circuitry? But he was moving on.) In some people, though, something causes these impulses to go haywire. The ventricles keep on doing their steady job (which is just as well, or things would go wrong very quickly for the heart’s owner) but the atria fibrillate–that is, they develop arrhythmic patterns of their own. “They’re basically just fluttering,” he said.

It wasn’t clear what had caused this epsiode of mine; it wasn’t clear what caused atrial fibrillation in general. He gave me a list of possible contributing factors: high blood pressure, hardening of the coronary arteries, recent heart surgery, chronic lung disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathy (a disease of heart muscle that causes heart failure), some miscellaneous congenital defect, a pulmonary embolism (that is, a blood clot in the lungs), a hyperactive thyroid, pericarditis (an inflammation of the outside lining of the heart–uncommon), excessive use of alcohol, caffeine or cocaine. “Do you use cocaine?” he asked, peering at me for signs of decadence.

No coke—in fact, none of these sounded likely. It wasn’t at all clear what had caused this attack. It also wasn’t clear what would happen next. Now that I had had this episode, he said, the chances were that I would have more–worse attacks, more often. One possibility for treatment, he said, was that I might have a new and somewhat experimental procedure called oblation.

“Oblation?” I repeated, spelling it out, thinking of the General Oblation Board in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials. He nodded. This was bizarre, I thought. In religious terms, oblation is an act of offering something–praise, worship, thanks, one’s heart–to a deity. If I underwent this procedure I would literally be placing my heart on the altar of medical science.

Later, when I went to WebMD, I found that the operation is actually spelled “ablation,” but it was no less terrifying than, say, laying oneself on an altar and opening one’s shirt for the knife.

“There are two types of surgery that can be used to treat…atrial fibrillation,” WebMD announed, referring to atrial fibrillation by its chatty medical name of A. fib. “These procedures are often combined with other surgical therapies such as bypass surgery, valve repair, or valve replacement.”

Wait a moment. Isn’t that what they call open-heart surgery?

WebMD suggested two possible procedures for A. fib. One was the Maze procedure. “The surgeon makes small cuts in the heart to interrupt the conduction of abnormal impulses and to direct normal sinus impulses to travel to the atrioventricular node (AV node) as they normally should. When the heart heals, scar tissue forms and the abnormal electrical impulses are blocked from traveling through the heart.”

The other procedure was called surgical ablation. “The surgeon creates controlled lesions on the heart and ultimately scar tissue to block the abnormal electrical impulses from being conducted through the heart and promote the normal conduction of impulses through the proper pathway. This procedure involves a single incision into the left atrium. One of three energy sources may be used to create the scars: radiofrequency, microwave or cryothermy (cold temperature)…..”

I couldn’t read any more. I expected to have a myocardial infarction on the spot.

* * *

For right now, the doctor ordered me an IV drip and a medication called diltiazem, which would at least slow down my stampeding heart. After that, they’d just have to see what happened. With luck, my heart would return to its normal activity, called sinus rhythm–not after the cavities in one’s nasal passages, but after the up-and-down sine wave that appears on the cardiac monitor.

If the fibrillation continued, he said, they’d probably have to give me blood thinners. If my heart kept on beating erratically, blood would mill aimlessly around the atria rather than being regularly discharged. Some of it might pool at the walls, like sticks circulating in small pools at the bank of a river, and form clots. One of the clots might break loose, wander around my bloodstream, lodge in my brain and cause a stroke.

“Now, that’s not going to happen in the next few days,” he went on, but his tone and look were a clear warning.

While I waited for the diltiazem to take effect, someone was admitted to the next bay, invisible on the other side of the curtain. Half-listening to him talking, his voice shaky and dejected, with his doctor I realized with a shock that this guy, too, had been admitted for atrial fibrillations–yet his had apparently been coming back for months, even years.

“I’ve had ablations, but it always seems to come back. It’s a pain in the ass.”

For over an hour I heard him muttering and complaining, and it felt like a message from the future. At some point he, too, must have had his first attack, probably a playful, odd episode like mine. Maybe he was scared; maybe he thought nothing of it. But it had come back again and again, and now the cutting-edge science was no longer working, and he had been reduced to this fidgeting shadow of himself, unable to tell even when his heart was working properly and when it wasn’t, perpetually a stranger to himself and his natural rhythms.

* * *

The electrodes kept coming unstuck, the monitor kept issuing its alarms, and eventually a nurse appeared from my neighbor’s cubicle, turned it off, and asked me what I was in for. I told her about the fibrillation. She was professional, brisk, dryly humorous about the whole thing.

“They didn’t shock you?” she asked, in mild surprise.

“Shock me?” I thought I knew what was coming, but I had to put it off as long as possible. “You mean by showing me the bill?”

But the joke was on me. She chuckled and went on, “No, they sedate you and try to shock your heart back into its normal rhythm.”

I had run out of jokes. On the one hand this whole episode was not high drama: I was just lying around listening to the monitor and reading, of all things, a magazine dedicated to the ukulele. But now, it seemed, some frightening scripts were awfully close–the paddles on their wires, the shout of “Clear!” the body twitching helplessly on the gurney. My image of the barrel of monkeys was starting to seem absurdly naive.

For whatever reason, they decided against the electricity. A technician tugged the electrodes off my chest, each one tearing out a dozen long hairs. It was the only pain I felt all evening.

I got home around midnight. The racing, exhausted feeling had ebbed, but I still felt like a disconnected mechanism, a box of cogs that didn’t fit. Lying down was the opposite of relaxation: bed, like the bath, made it only more apparent how wrong things had become. I went upstairs and slumped on the couch.

The sounds of the puppy barking woke me up. The girls were coming upstairs to let her out, and I opened an eye. Maddy was looking to see if I was awake. “Hi, Daddy,” she said, climbed over the back of the coach and curled up with me. I ran an internal check and found that a calm had settled in my barrel. No, not even a barrel: my chest had returned to its normal size and flexibility. I barely noticed my heart: it was unobtrusively doing what it was supposed to do, a good servant, a unified set of forces. I didn’t need to lose any more chest hair to know that I was back in sinus rhythm. The sun was already above the hillcrest, filling the valley with light.

Even so, my sense of myself had been shaken in ways I hadn’t known existed. I found myself joking about the whole episode, but at the same time I felt as if I were walking with my head cocked over and one ear turned toward my heart. I noticed that every so often–a few times a day, maybe–my heart produced the slightest irregularity, not the barrel of monkeys but a single cardiac hiccup, then back to business as usual. When I felt a sneeze coming on, I had the sudden sense that as I sneezed, my heart would burst. A few days later I felt a muscle twitch in my thigh and wondered if this was a different kind of fibrillation, a sign of a more general series of faults in my wiring.

* * *

The day after my attack, by a strange coincidence, NPR broadcast an interview with Jae Sinnett, a jazz drummer and composer who had suffered heart palpitations after a prolonged bout of food poisoning. Being a drummer, he said, he was in tune with rhythm in general, even his own body’s rhythms, so he knew something was wrong, and checked himself into hospital. He ended up composing a piece based on the experience, a track called “Palpitations.” The beat shifts back and forth between 7/8 and 6/8, he said, and the chorus is in 5/8.

I listened to it, and it was certainly interesting, but it wasn’t like fibrillation. To score my heart would have taken every meter in the book, it would have included only one beat in a measure full of rests that were anything but rests. It would have included dotted notes and random syncopations. It was anything but musical. If a jazz band had played it, the nightclub patrons would have stumbled on the dance floor, turning in bewilderment and unease. Anyone eating would have felt queasy; anyone drinking would have stared at his glass in shock and dismay, would have sworn off the stuff there and then.

* * *

At soccer the following Sunday I began to discover just how common it is to have a faulty heart. Two of the guys lacing up their cleats next to me told me they had prolapsed microvalves, a condition that, bizarrely, is apparently not serious in itself, but it can mean that a visit to the dentist, of all things, can be fatal. One friend, in a subtle blend of compassion and one-upmanship, told me that he had had a bout of atrial fibrillation that went on for months. He stood up and began stretching his hamstrings. “I had to wear a heart monitor,” he said, patting his chest as if showing off a medal.

Later I read that Senator Bill Bradley developed A. fib. for no apparent reason and twice had shock treatment, technically called cardioversion. George Bush Senior developed A. fib. as a result of thyroid disease. Vice-President Dick Cheney had had a defibrillator installed because of erratic heart rhythms. Half a million Americans each year are diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. It is the most common form of heart trouble–yet there’s no clear understanding of what causes it, and no cure.

I was damned if I was going to let one evening in the ER stop me playing soccer. At first I took it very carefully, hanging back in defence, stretching, trotting on the spot, listening to my own vital signs. Someone had said that dehydration was a potential factor–all of a sudden, everyone was a heart expert–so I kept taking swigs of tepid water tasting of blue plastic. After a week with no exercise I wasn’t at peak fitness, but I didn’t seem to be about to collapse. I made a few experimental runs upfield with no ill effects, and after an hour was playing striker in my usual ambitious, clumsy way, sliding to try to reach a cross, diving for headers. We played for more than two hours, longer than usual, before people were looking for an excuse to call it a day.

“Play to the next goal?” someone called out.

“How about playing to the next cardiac episode?” I called back.

* * *

The heart is a perfect organ for jokes. A heart attack is so sudden it has the effect of a punch line. A Jewish friend, not knowing what had happened to me, sent me a joke:

Six retired Floridians were playing poker in the condo clubhouse when Meyerwitz loses $500 on a single hand, clutches his chest, and drops dead at the table. Showing respect for their fallen comrade, the other five continue playing standing up.

Finklestein looks around and asks, “So, who’s gonna tell his wife?”

They cut the cards. Goldberg picks the two of clubs and has to carry the news. They tell him to be discreet, be gentle, don’t make a bad situation any worse.

“Discreet?” Goldberg protests. “I’m the most discreet person you’ll ever meet. Discretion is my middle name. Leave it to me.”

Goldberg goes over to the Meyerwitz apartment and knocks on the door. The wife answers through the door and asks what he wants. Goldberg declares, “Your husband just lost $500 in a poker game and is afraid to come home.”

“Tell him to drop dead!” yells the wife.

“I’ll go tell him,” says Goldberg.

Boom-boom.

Yet the heart was turning out not to be like that–healthy one moment and sayonara the next–at all. Judging by the stories I was now hearing from all sides, hearts everywhere were fluttering, twitching, missing beats, softening, hardening, silting up, their valves leaking or not closing properly or slamming shut so hard they swung through their seals like a swinging door in a restaurant kitchen.

And even the ultimate punch line, the drop-dead heart attack, had lost its punch. Another email came in, this time from guitarist/historian Dick Stewart in New Mexico. He’d had a heart attack and triple-bypass surgery but was now back in circulation, so to speak, feeling mostly stupid for having smoked for fifty years, and also feeling a bit depressed, which he had been warned was the modern-day outcome of the event that for most of history had left you like the proverbial doornail.

The heart had lost its fabled carthorse strength, that tireless labor that lasted a lifetime–but it had also lost some of its sudden-death fragility. It just kept going, abused and ignored, doing its job as best it could. It was the most human of organs.

* * *

Dr John Fitzgerald, my cardiologist, turned out to have dark hair and a beard going grey, an ample belly from which a soft but deep voice rumbled, an attentive and courteous manner, sly humor. He repeated the definitions that were now familiar, sunlight falling through the slatted blinds of his suburban office, a world away from the emergency room.

“We want to check the echocardiogram,” he said, “to see if there is a leaky mitral valve that might be predisposing you to having this.

“The natural history of this, over the years, is that it may not occur again for a long time. It may never occur again. Sometimes it comes back, and then it comes back more frequently, and then it becomes the dominant or established rhythm.

“We do have various ways of dealing with it. There are medications available that may prevent it from recurring, and more recently there has become available a type of surgery that modifies the conduction capacity of the heart by creating little tiny burns in the side of the heart with a special radio-frequency catheter.”

“Is that ablation?” I asked nervously.

He nodded. “That may help to prevent recurrences. That’s usually something that is reserved for people who are resistant to medication–or resistant to taking medication.” He chuckled ruefully. “It’s not something that we generally offer to somebody after their first go-round of this stuff, but if it seems to become more of a problem, it’s certainly a consideration. It’s a bit on the cutting edge. It’s a bit experimental. But there’s a couple of doctors at the Fletcher Allen who seem to be doing pretty well with it. They may be able to help us out if it should be necessary.

“The Holy Grail of cardiology is atrial fibrillation,” he said, and laughed. “If I could invent a cure for atrial fibrillation I would probably be the richest man alive and the best-regarded among cardiologists.” He chuckled heartily at the thought.

* * *

He sent me off to get an echocardiogram, an ultrasound of the heart. The technician had me take my shirt off and lie down, affixed three sticky contacts to my chest, squeezed lubricant onto the business end of a short white electronic wand attached to a computer set-up, placed the wand firmly on my chest in the hollow just to the left of my sternum, and looked expectantly at the two monitors.

I had seen ultrasounds before in the months before both my daughters were born, had watched that mysterious treasure hunt through perplexing sooty shapes that suddenly reveals a hand, or a foot, and then a whole pale being tumbles into view, curled as if asleep or deep in thought.

This picture was quite different. At first the strange mouth-like shape opening and closing in the darkness looked like an undersea creature of some kind, perhaps a large, hyperactive sea cucumber. But as the technician moved the lubricated wand here and there on my chest and the image became more defined, it was clear that what we were seeing was something that had never existed in the visible world, exposed to air or water.

I’d never thought about it before, but living creatures clearly have well-sculpted, purpose-built external surfaces, sometimes hard for protection, sometimes streamlined for efficient movement. The surfaces that we present to each other, and to our surroundings, have a kind of sleekness about them.

What appeared on the monitor clearly didn’t need to bother itself with externals. It had committed itself to being fleshy–that is, packed to swelling-point with life and purpose.

The cartoon heart has a simple outline, a steady shape. The thing on the monitor couldn’t wait around for definition, like a Victorian businessman too impatient to sit for his silhouette. It was working away, every cell, every syllable clenching and unclenching–not like a fist, which tends to close and open with a single sense of purpose, unified by the rigidity of bone, but in a much more complex and subtle way. The heart is a muscle, we are taught in school, but this was more like many muscles, an amazing collaboration of muscles, working not only together but in several different directions, and working, what’s more, at amazing speed. I was lying down, not particularly anxious, and my pulse was maybe 63 or 64, yet this consortium of rubbery-but-intelligent tissues was galloping along. The average heart beats some three billion times, yet the heart is the only muscle that unless damaged or diseased does not weaken with age. It seemed impossible to believe that one organ could do so much, so quickly, for so long. It seemed impossible to believe that it could do so with me barely noticing it.

Yet that was just the start of the voyage. The technician moved his mouse, tapped some keys, drew some lines on the screen to measure the thickness of this, the size of that, moved the contacts to different places on my chest, moved his wand down below my ribs and up to my throat, and finally settled on a view that looked vaguely like a large nose, seen from below and looking up into the nostrils, but which I knew must be a full-profile internal shot of my heart.

The twin dark caves were the ventricles, the larger, lower chambers that contracted regularly, pumping the invisible blood so forcefully it made the journey around my vascular system, a network so long that if it were extended it could be wrapped two and a half times around the Earth.

The smaller chambers, only partially in view, were the atria, currently behaving themselves and playing their part in this astonishing coordinated dance of muscle.

In the middle of the screen, though, was something else, something that moved more rapidly than anything else in this cardiac gallop. The wall dividing the left chamber from the right ran roughly up and down the screen, and two-thirds of the way down this whitish divider a strange flapping was taking place. Two absurdly small wings–chicken wings, I thought–were beating up and down in that sinuous, unified motion that birds’ wings obey, only with an even greater range of motion up and down. These, I realized with a shock, were the reason for the echocardiogram. These were the tricuspid (right) valve and the mitral (left) valve, and they were two of the most astonishing things I had ever seen.

If I had ever thought about heart valves before, I had probably thought of the valves in a car’s engine, opening and closing like little metal lids. Rigid, in other words, and tough because they were rigid. These winglets seemed far too pliable to work as valves, so flimsy they bent up and down wildly in the current of blood, yet strong enough that when the ventricle squeezed its dark chamber, they sealed shut, and the blood shot out through the aorta or the pulmonary artery instead of back up into the atrium.

And my own valves, no matter how flimsy or frenzied, seemed to be functioning just fine: the technician hit some keys and the computer, having used its measurements to calculate the amount of blood flow, suddenly superimposed flashing patches of vivid color–blue and red, with spots of white–on the heart’s dark and active chambers. This was the machine’s artistic impression of the activity of my invisible blood. Blue and red, the technician told me, were good; they indicated blood being pumped in the usual and healthy manner. The white blips were signs of leakage, of tiny amounts of blood being forced through the valve back into the atrium.

“Insignificant amounts,” he said, his eyes fixed on one screen, then the other. A heart murmur, but an almost inaudible one.

Looking at those wing-like valves beating impossibly quickly, it was easy to think of the heart as a miracle–and in fact proponents of Intelligent Design have a great deal to say about the heart. But the chambered heart developed, astonishingly, from a basic squeezable tube found in simple life-forms such as worms. It developed, moreover, when the first creatures left the ocean and became terrestrial. In short, the heart, as much as the lungs, is a land organ. And for all its astonishing complexities, when looked at closely it shows every sign of being riddled with mistakes, bad ideas and evolutionary dead ends. In one not uncommon congenital condition called Tetralogy of Fallot, the unborn child’s heart develops with the aorta attached in the wrong place. Variety is a human condition. The heart is a work in progress.

Above all, I had a new understanding of rhythm. If I had thought of the heart before, I had thought of it as a pump in the industrial sense, a fleshy device with a single purpose: to keep beating. Now it seemed to me that the atrioventricular node, as much as the brain, was constantly making decisions, taking into account who knows how many sets of incoming, often contradictory, information, adapting and adjusting from one beat to the next, as alert and supple as—well, a conductor, I suppose, listening to a hundred players but knowing the score, knowing too that life involves constant variety, flirting at every beat with chaos but denying it steadfastly in a thousand different ways.

What we think of as calm is in fact rhythmic; the steady pulsing of light, sound, magnetism and electricity. The deep beating of the ocean. The dance along the artery, the circulation of the lymph, wrote Eliot, are figured in the drift of stars. Diurnal, circadian, menstrual, annual. The heart manages a consolidation of all these rhythms.

The technician ripped the contacts off my chest two at a time and handed me a paper towel to wipe off the lubricant. A minute later I was out of that strange room, the room in which I had seen into—well, the heart of things. I was back into the world I was used to, a world of upright chairs and level tables, rectangular walls and floors.

It felt as if I had returned to a world designed by a more primitive geometry, rigid and simplistic, where everything was well-lit and clearly defined, a world without the slightest inkling of what rhythm meant, or of what life was capable of, especially when life itself was at stake.

And that was it, for the time being. Tomorrow I’ll tell you how this particular demon has returned.