Many of you were kind enough to write to me saying how much you liked my two previous anecdotes from Egypt, “The Camel’s Ass” and “Going Postal in Cairo.” Several more of you, or perhaps the same several, also said you’d like longer posts from me in future. So here, and for the next few Sundays, is the somewhat-more-complete story of my trip to Egypt. Or at least the parts you haven’t heard already.

First Impressions

Having arrived at the Longchamps Hotel in Cairo well after midnight, when I threw open the curtains in my room in the Longchamps Hotel I had no idea what to expect of the city. Perhaps palm trees. Perhaps the kites wheeling overhead that I saw in India and Pakistan. Instead, perched on the roofs of every house and hotel, tall and short, near and far, left and right, were satellite dishes.

I counted roughly 550. All beige, all tilted more or less the same way, they had the alertness and keen sense of purpose of anti-aircraft batteries, yet without any aggressive barrel they seemed benign, earlike. It was as if everyone in the city had signed up for a futuristic interstellar monitoring project, and was straining for sounds of extra-terrestrial life.

After gazing in astonishment for a few minutes it dawned on me that my legs, where the 9 a.m. sunlight was falling, were starting to burn. Sunburn at 9 a.m.? It didn’t seem possible. It was the title of a bad thriller.

I tottered off to breakfast, which had that small-European-hotel muttered-conversation feel, croissants and eggs and bad coffee, until I tottered back out of the breakfast room and saw a couple of people had taken their breakfast onto the potted-plant fifth-floor terrace. Sunburn and eggs at 9:30 a.m.. Couldn’t imagine it, myself.

The Longchamps had, of all things, a golf theme. Even some of the giant glass flower-vases sporting brilliant hybrid lilies had golf balls in them, as if life itself were a water trap. My room also had the world’s cruelest bath. It was no more than four feet long, and was divided into two halves, one of which was perhaps two feet deep, the other a mere nine or ten inches deep. In other words, all you could do was sit in the shallow end with your feet in the deep end. Impossible to take a nap in; impossible even to get your back wet. Rarely have I formed such a deep and consuming hatred for a domestic appliance.

Napped again, found out how to work the wi-fi internet, got the helpful guy on the desk to write out directions in Arabic to the World Health Organization office, which in his delightful transcription came out as World Half Organization, and directions back to the hotel, printed in Arabic and English on a card with a map. Maps are, of course, a Western vanity: the taxi driver used the time-honored method of pulling over every few minutes to call to someone on the side of the road and ask directions.

I was getting more and more excited. The novelty, the challenge that brings out the best in you—this is what travel is about. I was even starting to enjoy the heat, or at least to redefine it, to take it on as part of the journey: it was a badge of honor, even—given that it enveloped my whole body—a uniform.

Unlike the World Health Organization (WHO) country office in Karachi, Pakistan (which has been built on an unused bit of desert on the outskirts of town and my taxi driver couldn’t find it even when we were parked out front), the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office of the WHO is a marble monument, a cross between a mausoleum and a bank. Very reassuring. I could sense infectious diseases being daunted by its very façade.

My contact, Jane Nicholson, had kindly agreed to see me right before shooting off on holiday, and there was an air of great activity in her office, which included lists of publications in progress. I wish I had written some of them down: technical stuff, they tended to have titles such as “Incidence of Boll Weevil Fever in Rural Areas beginning with the Letter F,” and “Ground Water Testing Using Only a Cotton Swab and a Toothbrush.”

She herself had that English habit of saying “Yes,” and “Right, then,” to sum up and convert conversation into planning into action. She listened intently to my explanation of why I was in Egypt (an absurdly ambitious agenda that included learning about bird flu, teaching writing workshops to healthcare workers and trying to find interesting sites and good restaurants for National Geographic Traveler) and at once began to suggest a list of people I should see.

She was joined by her colleague Dr. Kassem Sara, a short man with a high forehead, an energetic manner and alert eyes, who had just returned from prayers.

Kassem had several endearing habits. Every time we were alone in his office he immediately asked, “Would you like something sweet?” and offered candies, freshly-baked breadsticks, tea, coffee. He also had that Arabic physical familiarity, taking my arm, guiding me into a room or an elevator. He was from Syria, he explained, pausing at a map to show Damascus, the road across the desert through the ancient city of Palmyra to his home town on the Euphrates. Right in the cradle of civilization, I offered. “Yes, we are very proud of that,” he said. But now he had been in Egypt for fifteen years and saw it as his home. Egyptians are friendlier than Syrians, he said, and besides, his children refuse even to visit Syria. I got the impression, though I may be wrong, that Egyptians see Syrians as a little behind the times, the site of an empire too ancient to count.

He also taught me to say “Bism’allah.”

“It is what we say when we begin something,” he explained. “It means, `in the name of God.’ You and I are beginning.”

“The French would say, `Allons-y!’” I said. I’ve always liked the phrase for its energy, its élan.

He nodded. “Allons-y!” he repeated, committing our collaboration to energy, and to God.

In the meantime, Kassem and Jane had drawn up a list of roughly eight dozen people I should meet. The eminence grise and collective memory of the organization, they said, was Dr. M. Haytham Al-Khayat, a teddy-bear of a man who was downstairs in an office the size of a library, sitting low in an armchair with that posture some academics develop in which they seem torpid but are watching everything that happens with such awareness that they observe the movement of microbes, and know the end of your sentence before you have thought of the beginning. He listened to what I said, but I could tell he knew it all already and was absently using the unused portions of his mind to play Tetris.

“Yes, but the person you must talk to is Dr. Zuhair Hallaj,” he said, with the air of one solving a chess problem involving checkmate in a mere sixteen moves. So Zuhair, the head of communicable diseases, was called in, and within minutes had grasped everything and was calling the head of communicable diseases at the Ministry of Health so arrange for me to meet him the following day.

Let me explain why this was a miracle in itself.

Much travel literature by Europeans features the author waiting in some dim and stiflingly hot governmental corridor for days waiting for the lowliest functional to return from lunch and stamp a crucial document that will, in a fashion that can only be described as Oriental Kafka, allow him to visit another governmental functionary who will likewise be out for lunch, but will finally return and stamp the document with a stamp that cancels out the first stamp.

These accounts are by no means exaggerated. To have me visiting someone barely below the level of the Minister on my first full day in the country was staggering. To tell you the truth, I was already a little daunted, and began wondering, in the corner of my mind usually reserved for Tetris, what on earth I should wear.

Kassem, meanwhile, was extending the mental list he was making of people I should meet. Even as their names came up in conversation I was starting to feel uneasy, all over again, about my lack of Arabic. Names they threw out sounded suspiciously similar to each other. I wrote them down, spelling phonetically, as quickly as I could—a method that, combined with my appalling handwriting, pretty much guaranteed future confusion.

Back at his office, Kassem offered me sweets all over again, and showed me some of his work, including a monumental project: a unified medical dictionary in Arabic, English and French. Knowing how much perception and understanding of disease is affected by the assumptions and history of one’s culture, I could begin to imagine the difficulties involved. Not to mention the fact that our understanding of disease is dynamic, changing so often and at times so rapidly that yesterday’s diagnosis is today’s lawsuit.

Kassem agreed, and came up with a subject that showed an entirely different range of difficulties. How were he and his colleagues to name clitorectomy, widespread in Africa? They wanted, frankly, to choose a word that was accurate but ugly, to indicate that the practice was repulsive to them. “Clitorectomy” sounded far too scientific, as if those practicing it had good medical reasons for doing so. “Female circumcision” likewise sounded too acceptable, as male circumcision is standard practice in both Jewish and Muslim faiths. Even to go with the phrase of choice, though—“female genital mutilation,” or FGM—posed problems, as religious conservatives might feel that by using such a phrase, the dictionary was implicitly criticizing male circumcision. (Fine by me: speaking as an uncircumcised male, I’d regard any assault on my foreskin as genital mutilation.) So the editorial team had to have a series of consultations with religious leaders, who (and Kassem sounded a little surprised at this) unexpectedly endorsed the FGM language. Shortly afterwards, perhaps by coincidence, the Egyptian government even came out and issued for the first time an explicit condemnation of FGM. The more I looked at Kassem’s robust volume, with its more than 100,000 terms unified in three languages, the more I imagine Dr. Johnson looking on and being pretty damn impressed.

My final act of the working day was to buy a cell phone, which I achieved with the help of no fewer than four guys at the Mobilinil office two doors down from my hotel. One told me of the virtues of the individual phones, and I argued him (“Simpler! Simpler!”) down to a Nokia that did not include a flat-screen plasma TV or GPS system. (Though it may include Tetris, come to think of it.)

He was the one who also showed me how to insert the chip. He, however, had no understanding of my question, “How do I pay for the actual calls?” This only evolved over time. He told me I needed a SIM card, but the one he installed spoke in Arabic, so another of the guys took over the task of making my new phone speak English, which was a Rosetta Stone experience that took ten minutes and left his thumb exhausted.

Somewhere in there I had to buy yet another card that seemed to be for actual calls once the phone was all chipped-up and chipper, and I got my actual phone number off something that looked for all the world as if Guy #3 was offering me a stack of free CD’s to choose from, all apparently identical. I was wrong about that, but they did then offer me a free Mobilinil backpack. Even this generous act confused me as Guy #1 had clearly been badly work down by my state of basic incomprehension of cell phone technology and he began to lapse into French, called the backpack a cadeau (gift). By the time the whole transaction had been accomplished, I half expected a new generation of cell phones to arrive by truck, making my Nokia obsolete. Then Guy #3, who had been in a kind of silent supervisory capacity until now, stepped in and advised Guy#1 how to create a receipt on the computer and print it out. Finally, I signed a contract that was completely in Arabic, so I may well have signed away my rights to a fair trial, or the Egyptian edition of my next book.

It finally struck me that Guy #4 had nothing to do with the transaction at all, even though he had been paying keen attention and, indeed, had offered his opinion in a polite sort of way every so often. He was the security guard. Every cell phone shop had one, as if Caireans were about to stampede off the streets and grab handfuls of Nokias—a ludicrous idea, as every Cairean already has a cell phone, and every one of them is more advanced than the pathetic little beige object I now possessed.

I walked out feeling immensely pleased with myself, but not as pleased (or as sensible) as the hotel desk clerk, who asked to see the phone, gave little chortles of glee, declared Nokia a good make, showed me how to access my menu and my messages, and finally did the most important thing of all: he called me on it, and we had a very jovial brief conversation on our cell phones, three feet away from each other across the counter. I now finally knew how to use the little techo-smidgen, and was so grateful I gave him the free Mobilinil backpack to pass on to his children. We both agreed it had been an excellent day.

That evening, I went out for a meal. That’s the short version. Here’s the long version.

I asked my mate the desk guy for recommendations. “What kind of food you want to eat?” he asked. Egyptian, of course, I said. Ah, he said, I should eat at Abu El-Sid, on El-Sayed El-Bakry Street.

Okay, so one thing I’ve realized is that the Egyptians have a very casual attitude to Anglicizing Arabic words. “Al,” which means “the,” is also spelled “El,” and is inserted before any noun. Or not. Even the restaurant, once I found it, called itself Abou El-Said outside and Abou El-Sid on the menu. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Finding it will not happen for some little while.

My mate the desk guy was a wonderful man, and no sooner had he recommended the restaurant than he knew he’d need to tell me how to find it, so he found a menu from his own hotel’s restaurant, tore a strip off it, and with great concentration began to draw me a map that already ranks among the masterpieces of Egyptian fiction. If I had followed it faithfully I’d have wound up in the Red Sea, or possibly the Gulf of Tonkin.

Luckily, standing beside him was another Egyptian guy. (All Egyptians are issued with another guy to stand beside them. They’re also issued with a cell phone, a carton of 200 cigarettes and a satellite dish.) This bystander was clearly an educated Egyptian in Western clothing with a sharp briefcase but, unusually, he spoke no English. Nevertheless, he spoke to my mate the hotel guy and said, in effect, that he was going past the Abou El-Sid and he’d walk me there. Triffic, sez I, and we head off to the lift.

On the way, incidentally, I walked through the metal detector and set it off. The metal detector was installed at the head of a longish corridor that led to the rooms, just past the head of the stairway, presumably to protect the desk clerk from anyone walking up five flights of stairs in ninety-degree heat who still had the energy to assail him. I set off the metal detector every time I went to the front desk. Nobody paid a scrap of notice. It could be a creak in the floorboards for all that it registered on anyone’s consciousness.

The lift was, as they say, a piece of work. Or perhaps half a piece of work. It had two broken lights and a button that read “Poussez,” and when it arrived and you opened the flimsy little doors it was the size of a pillowcase. Seriously. I discovered that I could stand on one foot, lift the other like a stork and, without moving, touch all four walls with my knee.

Actually, this was fine. The disconcerting feature was that the floor had buckled and lifted over time, so when you stepped into the lift the floor gave way two or three inches, and for a fraction of a second it felt as though the whole lift had given way and was falling with you toward the basement.

By the time we got to the ground floor, it was very clear that I was never going to have much meaningful conversation with my new guide. He spoke to me earnestly and with excellent eye contact, but of course like most Western travelers I hadn’t learned any Arabic at all. I was pretty sure he was saying, “You’ll really like this restaurant,” because after a thoughtful observation or two he said, “Aubergine! Aubergine?”

Yes, I said, I like aubergine very much.

Of course, even in this I was completely wrong. On the way to the restaurant, in the midst of pointing out landmarks crucial to Egyptian history, discoursing on the epistemological difference between knowledge and understanding and predicting the results of the next World Cup, he broke off in excitement, pointed, and announced, “Aubergine!” I looked. He was pointing at a shoe shop.

We headed off through the streets of Zamalek, a district of Cairo that occupies an island in the middle of the Nile. The hotel guy had said “Turn right, and then again right,” but we kept going right then left then right then left. Knowing it’d be dark by the time I finished eating (if I ever ate at all) I was looking out for landmarks. Aha! A Mobilinil cell phone store. Wait–another Mobilinil cell phone store. And another….

The streets got narrower. We passed several soldiers, whose job was to lounge handsomely and guard themselves, or, if in pairs, each other. As I passed one of their little posts I swear I heard a radio playing an Arabic version of “Louie, Louie.”

Even though the streets were all well equipped with serviceable, if slender, sidewalks, my companion walked down the road. Egyptians regard their sidewalks as if they were training wheels: as soon as you can walk properly you do so in the street with the big boys. Even though the open roadway, between solid ranks of cars parked down both sides, was barely the width of a car plus ten inches, Egyptians seemed to take the slogan “Share the Road” seriously. At one point a big BMW came toward us and honked, which I assumed meant “Why aren’t you using the slender but serviceable sidewalk, you morons?” but no, the driver knew my companion and was just honking hello. They passed so close that my companion could have hip-checked the BMW into a Pepsi stand.

Finally we made one last turn and my companion said, “Abou El-Said!” and pointed at a vast pair of wooden doors up a short flight of steps. He waved cheerfully, made a few last observations on the shortcomings of string theory, and strolled off.

In some confusion (as there was no sign, no menu, not even a light) I went up the stairs and pushed at the doors. One opened, and sure enough I was in a restaurant.

It was delightfully dim, lit by hanging lamps with perforated shades that cast scimitar-shaped slices of light on the stucco’d walls and pillars, and furnished with small, low, marble-topped tables and upholstered armchairs that looked antique–authentically so, as I discovered when I leant lightly on the arm of my chair and it snapped. Arabic music whirled out of speakers. The place felt utterly Arabic: it wasn’t actually a tent, but its ambiance was undoubtedly tentlike. Tentish. With a hint of tentativity.

I half-expected the menu to be in Arabic, and was practicing my imitation of a chicken and a lamb, but luckily it catered to both Europeans and smartly-dressed Arabs in Western jackets and slacks. Let’s see. I could have molokhaya (“Egypt national dish”) with chicken and rice, or rabbit and rice. I could have stuffed pigeon. Grilled quail. Chicken liver Alexandrian style. Hmmm. No wonder the skies over Cairo have seemed suspiciously empty to me. In the end I ordered a Stella, babaghanoug and molokhaya (Egypt national dish) with chicken, sparing the Egyptian rabbit population. The babaghanoug, served with slices of pita and toasted pita, was delightfully lemony and very light. I had finished the whole bowl before the spiciness caught up with my tongue.

In the middle distance a young woman, smoking a hookah, in Egypt called a sheesha, blew out a cloud of blue smoke so vast and intense it had its own meteorology. My main course arrived. I recognized the chicken and rice but it came, like the Mexican flag, flanked with two bowls of stuff, one green, one red. The red stuff tasted quite a lot like tomato soup. It was hard to think of tomato soup as the national dish of anywhere except the Kingdom of Campbell, so I tried the green. “Molokhaya” apparently means “edible green Nile slime.” Google told me that it’s Egyptian spinach soup, but it didn’t tell me that until I got back to the hotel. I took to dipping the chicken in the Campbell’s.

(Note: you feel entitled to criticize other countries’ cuisine when your own country’s culinary rating is #176 on the U.N. list.)

The check came in a nice little ornate lacquered box, as if it were really some kind of exotic drug paraphernalia. I like this city.

On the way back, religiously turning right, left, right, left, I came across Mandarine Koueider, a pastry shop on El Shagrat El Dor. Having not had dessert (as if that mattered), I took a closer look. The pastrychefs were working right at the counter, producing vast round plates of baklava-like pastries the size of bicycle wheels and then chopping them off for display, or for the customers who were standing at the counter and pointing. I did some pointing of my own and for ten pounds twenty-five piastres (about $2.15) chose four different honeyed pastries, two of them of phyllo-type flaky dough, two made of filaments like vermicelli wrapped around nuts, drenched in honey.

I walked back through the soft, hot Zamalek night, down the middle of the streets.

Many of you were kind enough to write to me saying how much you liked my two previous anecdotes from Egypt, “The Camel’s Ass” and “Going Postal in Cairo.” Several more of you, or perhaps the same several, also said you’d like longer posts from me in future. So here, and for the next few Sundays, is the somewhat-more-complete story of my trip to Egypt. Or at least the parts you haven’t heard already.

Many of you were kind enough to write to me saying how much you liked my two previous anecdotes from Egypt, “The Camel’s Ass” and “Going Postal in Cairo.” Several more of you, or perhaps the same several, also said you’d like longer posts from me in future. So here, and for the next few Sundays, is the somewhat-more-complete story of my trip to Egypt. Or at least the parts you haven’t heard already.

Thursday, July 24

The folks at the Cairo office of the World Heath Organization had told me that Egypt was suffering a national crisis in traffic accidents, and their concern became only too understandable as soon as I set off in a taxi to try to find the Ministry of Health—or, according to the handwritten directions thoughtfully provided by the desk clerk to hand to my taxi driver, the Ministry of Half.

The fault didn’t lie with the vehicles: despite the Egyptian’s grumbling about their traffic, I’ve seen far worse in Bombay, Karachi and Dhaka. No, the danger was the pedestrians. The habit of walking down the middle of the street that I had noticed in the quiet enclave of Zamalek didn’t seem to be limited to narrow back streets late in the evening. Even at the major traffic arteries just across the Nile into Cairo proper, with five or six lanes of traffic making their way at somewhere between a stutter and roughly 40 miles an hour, people in ones and twos waded casually through the flow, talking to each other. I expected to see a dozen crushed hips by noon.

Cairo’s roundabouts, by the way, are of the French rather than the English variety—in other words, instead of being simply a traffic-merging device, preferably with floral embroidery, they’re more like a grand square or place at which large amounts of traffic arrive from all directions and get into arguments. Architecturally, they have a wonderful sense of openness and discourse; functionally they’re a steady succession of disasters begging to happen.

The Ministry of Half turned out to occupy more or less an entire city block, which my driver manfully circumnavigated two and a half times looking for the front door and cross-examining a dozen different expert witnesses on the sidewalks. Eventually he dropped me off on one flank, encouragingly said, “Green door!” and left me to the mercy of ten thousand Egyptians, almost none of whom, as it turned out, spoke English.

The Green Door entrance was clearly the entrance for the commoners, who were streaming in and out in large numbers, most wearing the traditional ankle-length galabiyeh, or light cotton robe, rather than western dress. The interior entryway was dim and very basic, lacking in any furnishings or decorations, and for the first time I felt as if I were back in Pakistan.

My job was to visit the director for communicable diseases, a Great Man way up in the ministerial stratosphere, so I was pretty sure people would know who I wanted and where his office was. I pulled out the piece of paper on which I had written, phonetically, “Dr Amr Khandil,” and already began to see the shortcomings of phonetics. I was pretty certain that’s how Zuhair Hallaj had said it at the WHO office the previous day, but Maytham Al-Khayat had quipped jovially, “Khandid is candid,” so I thought maybe it wasn’t Khandil but Khandid. The final consonant is pronounced very lightly in Arabic, so anything was possible.

I went over to one of the ministry workers in their blue shirts and neat charcoal slacks and said, “Dr Amr Khandil?” I wasn’t confident of my Arabic pronunciation, but I was at least confident that they would know the Great Man, and would usher me swiftly to his presence.

He looked hesitant, then a light went off. “Ah! Amr Khandil!” I nodded. He called over another guy who could apparently be spared at a moment’s notice to help this ignorant Westerner, spoke rapidly to him, loaned him to me, and the two of us headed out across a courtyard, up a lift that had evidently been designed by the guy who installed the one at the Longchamps—perhaps even de Lesseps himself—and down a series of slightly tawdry corridors to a closed door, on which he knocked. The door opened. A meeting was in progress. One of the guys at the table was summoned to the door. He looked startled. I introduced myself. He looked both startled and baffled, though the bafflement was beginning to win out over the startlement and take him in the direction of complete paralysis. He called out a colleague who spoke some English.

“This is Dr Amr Khandil,” said the colleague, whose own specialty was bewilderment.

Hmm. Clearly not the right Amr. “Director-General of Disease Control Management,” I risked in English.

They digested the syllables one by one, looking at each other. Then light broke through. “Ah! Amr Kandeel!” In other words, K as in K, rather than Kh as in that gutteral Kh sound at the back of the throat. I was crushed. I was so proud of myself for being able to pronounce that sound.

Suddenly it all made sense—to them, at least. The could-apparently-be-spared-at-a-moment’s-notice guy was given instructions. His brow, too, cleared. Grins all round, though my grin was tempered by (a) relief, (b) sweat, as the temperature was already well over 100, and (c) embarrassment at having completely disrupted a meeting that was probably going to save several dozen lives.

We left the building, rounded a corner to the palatial front of the edifice, entered another, much grander door and there we were: a cluster of eager young staff looking up speaking English, knowing Dr Amr Kandeel and expecting me. And the short corridor outside his office was air conditioned, which made me very aware of the soaked shirt sticking to my back. All was well, and for the first time I even got to drink a demitasse of genuine Egyptian coffee: after chewing through the floating sediment I got down to the good stuff, which tasted rich and complex, like history itself, but flavored, I think, with cardamom.

The actual visit with Amr Kandeel is now rather a blur. I explained Writers Without Borders and our writing workshops, in which he expressed strong interest. I asked him about the pressing public health issues facing Egypt, and he agreed that avian influenza (which they call AI, at first confusing me because I thought they meant Artificial Intelligence) was a top priority. He pulled up a Powerpoint on AI, found that it was in Arabic, and talked me through it.

It was a sobering recitative. Egypt has been grappling with AI in its fowl-to-fowl and fowl-to-human form for two years, the country has the third-highest number of infections in the world, the virus has a 50% mortality rate, and above all Egypt has started a whole raft of education and social-change initiatives that certainly have not been tackled in the U.S.

We have a great deal to learn from Egypt, I told him, and said that I wanted to make AI a major topic of investigation while I was in Egypt, so I could go back and make presentations to the secretaries of Health and Agriculture of my state, and to the trustees of my college.

He gave me some more information in print and on CD, invited me back in a couple of days to meet some of his staff and learn more about AI, and as we shook hands I felt that even if nothing else came of my visit, this AI avenue would make it all worthwhile.

By the way, the sheer fact that I sat in his office for an hour was something of a miracle. Those travel books in which the author sits in a corridor day after day, week after week waiting for some obscure functionary to sign a form that then will need to be taken to another functionary who after weeks of delay will sign another form that countermands the first one—those are all true. For me to get in to see the top physician in the Ministry of Half the day after I arrived….well, it’s unheard of. I’m still stunned.

In the early evening: drinks with Richard Hoath, an expatriate Brit who had come to Egypt to work for an oil company and was now teaching in the Rhetoric and Composition Department of the American University of Cairo and writing a natural history column for the magazine Egypt Today. We talked about academia, about possible collaborations, about his students (some of whom speak several languages, and are enormously rich), about the district of Zamalek (which was originally a diplomat’s enclave, and ordinary Egyptians needed a pass even to enter the island) and about writing.

Most importantly, he made it clear that the default beer in Egypt is Stella, not Stella Artois but a similar beer brewed in Egypt. Beer was first brewed all the way back in Mesopotamia, though I can’t say that this extensive heritage has made Stella the Pyramids or the Sphinx of beers.

Beer is also mentioned in the Epic of Gilgamesh, according to Wikipedia, in which the ‘wild man’ Enkidu is given beer to drink. “…he ate until he was full, drank seven pitchers of beer, his heart grew light, his face glowed and he sang out with joy.” Can’t say I sang out with joy, but it was nice to have someone to chat with in the evenings, which for me are always the hardest part of travel.

Then off to have dinner at L’Aubergine, which turned out to be a real restaurant after all rather than a shoe shop, for dinner. Took me some time to find the place, given the strangely haphazard Egyptian attitude toward signage: its formal street address was #5, despite the fact that there were at least a dozen buildings between it and the low-number end of the street, and that there were apparently several other buildings, including an apartment block, also numbered #5. This was yet another indication that Egypt works by a Higher Math than the West. In Arabic numerals, the 5 is written as 0. Didn’t the Arabs invent the zero? If so, why give it to the five? I was struggling, here.

L’Aubergine had very much the chic minimalist anything-but-Egyptian décor that hip young Egyptians seem drawn to: it could just as easily have been in Montreal. Soft jazz, rather Paul Winterish, on the p.a. Half the menu was vegetarian. Given the name of the place, I had to go for the moussaka. It was fine, though nothing special. Day Two complete, and I was still waiting for a great Egyptian meal.

Friday, July 25

My God! Clouds!

I’d been gaily assuming that Cairo was like San Diego and had climate rather than weather, but this morning the sky was riddled with clouds! Quite a bit cooler, too. Whatever next?

Slept badly again, then realized I had to move hotels as my opening-gambit booking at the Longchamps was now up. I chose the Horus House Hotel, one floor down, just so I wouldn’t have so far to lug my stuff (hmm. Luggage. That which one lugs?) and came one floor down the cranky lift.

Horus, it turned out, was the hawk-headed Egyptian deity. Aha! So that was the insignia on the tail of Egypt Air planes: the eye of the divine hawk. So much my for my theory it was a gigantic elaborate goldfish.

Moving made me feeling immediately better. Just the change of scenery, no longer looking at that hard single bed I’d come to hate, the tiny, mocking bath I’d come to despise. Then the front desk manager of the Horus said, “You are musician?”

Surprised, I nodded. “I’ve got my guitar here,” I said, patting behind my back. “How did you know?”

“I see your nails,” she said.

I was impressed right away, but even more impressed when the porter led me to my room. It had already struck me that mathematics, which first sprouted and flourished in Egypt (“algebra” and “algorithm” derive from Arabic words), was a very different plant in its native soil, much more complex and intricate.

At the Horus, this fact was true to the nth power. We headed into the depths of the building, and then the porter, carrying several of my bags, turned left. Down a shorter, dimmer corridor, then left again. Then left down a still shorter, still dimmer corridor. Then left again. Then again. How was this possible? The interior of the Horus was clearly a Singularity, or some other point where number, geometry, even space itself were constantly being created. Finally, string theory and multi-dimensionality made sense to me: according to the string theorists, there are not three (or four) dimensions, but seven, eight, nine, or even eighty-four. The theorists are reportedly confident that these dimensions exist, even if they can’t be found–they are just curled up somewhere, impossibly tiny. Ladies, gents and Members of the Acdemy, I know where those dimensions are. They are in the Horus House Hotel.

At the tiny, coiled heart of these dimensions, or of any labyrinth, is (according to the Greeks, who certainly knew Egypt pretty well) the omphalos or navel of the world. And such was the case, more or less, at the Horus: when finally I found my room, I discovered, weeping tiny whimpers of joy, that it had a bath. A full-sized bath! Well, a standard shower tub bath, but even so, I was like Speke seeing Lake Victoria for the first time. I felt like sobbing with joy. I felt myself going back in time. To my childhood, possibly even the primordial ooze. Excuse me while I regress, I thought, sinking into the suds.

1 p.m. Time for prayers: the muezzin was calling somewhere outside my window—very mellifluously, actually. I wondered whether centuries of tradition had taught muezzins what pitches to hit in order to have the greatest broadcast range. The campanology of the human throat.

The Horus was furnished very differently from the Longchamps upstairs, which had a recurring golf theme and catered far more to Europeans and North Americans. The Horus had a dark wickerwork lobby/lounge/bar area, beyond which the Higher Math corridors divided and wound away into mathematical uncertainty (emphasized by the astonishing fact that the 200 rooms were in fact on a lower level than the 100 rooms), carpeted in a swirl of earthtones…. Well, silt-tones perhaps. It was as if the annual miracle of the flooding of the Nile reached just to the fourth floor of the Horus, permeating the carpet. When I walked out of my room and glanced left, the adjacent room was open and I saw a very statuesque woman wrapped in a towel, standing in her bathroom as if in a throne-room. There was clearly a water theme going on here.

Took a taxi to the Egyptian Museum. In one of the side-streets, an awning had been spread from side to side about ten feet off the ground, and the shade beneath it was packed with the faithful kneeling in prayer. Another group was praying in the shade of the overpass by the river. I hope the Q’ran specifies praying in the shade, given the climate. All in all, further evidence that Islam is a religion born of a tent civilization in a hot land.

Having read the Lonely Planet guidebook’s warnings to tourists visiting the museum, going there was like rounding up the usual suspects. First there was the guy outside the museum who tried to tell me the place was closed (this despite the fact that he was standing next to an Open sign and a policeman) but while we waited for it to open, he said, he’d be glad to take me elsewhere and show me all kinds of other sights. Then there was the (female) tour guide just inside the gates who kindly showed me that I had missed the ticket window, but then tried to leverage this favor into the right to offer me an entire tour of the museum at LE 150 an hour, which is probably more than the Minister of Antiquities makes. Getting rid of her was like shaking bubblegum off a shoe.

The museum was neither as glorious nor as messy as I’d been led to expect, but it had an unusual approach to climate control: in an attempt at historical verisimilude, it recreated the climate of the banks of the Nile. I watched a tour guide, leaning over a sarcophagus, describing a particularly brutal event in Egyptian in history in passionate French, and his face was scintillating with sweat.

While the basic layout had been thought through there was still a sense that several thousand artifacts had been parked here and there, often without explanatory text of any kind, just because a space was available. All the same, the place had a creepy magnificence, especially in the main hall, dominated by vast pharaonic statues and tombs, and it was fascinating to see how the third dimension gradually evolved in Egyptian statuary over thousands of years: what began as etchings in rock steadily took on more and more depth until the figures stood half-in, half-out of stone, before emerging altogether and standing alone. (It was also fascinating to see that the statuary didn’t feature hair until the Greco-Roman period, when suddenly headdresses are out and everyone is bristling with hair.) It was a great illustration of the fact that, much as we’d like to believe in dramatic and original strokes of inventive genius, most ideas evolve bit by bit, restrained by tradition. Let’s face it: the fact that most statues of pharaohs look almost identical suggests that any sculptor who made his subject look either worse or better than the previous ruler in the dynasty stood a fair chance of being disemboweled and mummified on the spot.

In general, though, the level of skill and art was far higher than I’d expected for such an ancient civilization. A statue of a hippo god in particular was spectacularly convincing and cruel. And there was a humanness and a warmth that made the Graeco-Roman era statues, when they finally arrived, seem beautiful but cold. Some of the earlier figures called out to be stroked on the cheek.

Outside the museum I was greeted enthusiastically by a young guy claiming to be an English tutor who turned out to have a very strong interest in having me visit a papyrus-painting shop across the street from the museum. As soon as he had turned away another man, older, with a lean, weathered face, ran up to me and told me never to go into a papyrus-painting shop with a guide, as the final price would be bound to include the guide’s commission. He, on the other hand, could offer me up to 60% off the papyrus paintings in the next shop, “because today I am a little bit crazy.” At once, I thought of him as Eddie. He rolled his eyes and wagged his head. Both these hucksters threw in entertaining bits of improvised autobiography: daughter in Australia, friends in Piccadilly Square. I treated them as if I were genuinely grateful for their company and their conversation (which I was) and as if they were sincere in all they said (which they might not have been). So we had nice little chats on the hot sidewalk until they finally grasped that I wasn’t going to buy anything, at which point they gave up. I love this city.

Later it struck me that we westerners have a profoundly different view of making up our minds—how it happens, what it means. We tend to think of making up one’s mind as an individual act, in which we may consult others or ask advice but in the end the mind is made up, and that’s a position we expect others to acknowledge and respect. I wonder if in other cultures there’s simply a different view—that what we think of as making a decision is seen more like expressing an opinion, essentially an invitation to others to chip in and start an intellectual free-for-all? One reason why we find touts so offensive is that they violate our sense that we have the right to make up our own minds, or even to own our own minds. This might just be a misunderstanding, a mistaken view of the nature and mechanics of decision-making.

Even though my knees were killing me, I decided to walk back to the hotel to acclimatize myself to the heat. Made it in stages. The Egyptian Museum is in downtown Cairo, which is just across the eastern arm of the Nile from where I was staying on the island of Zamalek (or El Zamalek, of course, or Al-Zamalek, given the carefree Egyptian use of the definite article).

On the Zamalek bank were moored what looked like casino riverboats with gaudy names like Nile City and The Imperial and Omar El Khyyam and Caesar’s Palace. (Okay, I made the last one up, but it would actually be pretty appropriate, thematically and historically.) I decided to check one of these out and was welcomed at the gangplank by a girl dressed exactly like the cruise director of the Love Boat. The place was actually a cluster of chain restaurants including Chili’s. She ran through my options, and came to one that she described as “Oriental, including Egyptian.” Okay, I said, I’d go with that one.

I was the only European in the place—a condition I love almost without reservations. I chose an outside table by the rail overlooking the Nile. The manager himself must have been told a Westerner was on board, as he came rushing out and greeted me as if we were at Vegas and I were Tony Bennett. I had a very slow, leisurely lunch to enable my knees to recover: a very nice bread, puffed up like poori but less oily, much smaller and lighter than pita, served with spiced cream cheese and olive oil. Then chicken tandoori strips on a bed of spinach. It was generic but not bad at all. I tried to remember what the place reminded me of. Eventually, I got it: it was like an Egyptian TGIFriday’s–a phrase that, with the muezzin calling the faithful to their holy-day prayers in the background, was spectacularly literal.

More higher math. The Horus, I discovered, has a third floor, and indeed the way to get from the first floor to the third is by going through the second. Fair enough. But the third floor is, in fact, on the same level as the first floor, thus suggesting an equation of 3=1>2.

Gone were the sunny days when I could think of numbers as occurring at predictable intervals along a straight line. The more I looked around me, the more the traditional axes of number began to curl up, like the tentacles of octopi. By earnestly studying taxis and their registration numbers, I’d discovered that an Arabic 9 is pretty much the same as a European 9, and ditto the numeral 1. But the two is backwards and missing its foot, the three is lying on its back and has a long tail, the four is like a backwards three, the six is suspiciously like a seven, the seven is a V and the eight is an inverted V. Most confusingly, the five is written as a zero, and there doesn’t seem to be a zero at all! Was it any wonder the Horus is a series of mathematical paradoxes?

The number puzzle continued in the evening, when I went off in search for a restaurant called Crave, which is at 22A Dr Taha Hussein Street. I found the street easily enough, but after walking for some time, with the street getting darker and me stumbling every so often over tree roots and broken paving stones, I began to wonder. Many of the shops and homes didn’t have obvious numbers anyway, and when, after five or ten minutes’ walking I found a building numbered 10 (Western 10, not Arabic 10, which would be 15) I started to wonder which way the numbers ran. I pressed on, with vast, dark, sometimes vast decrepit mansions looming up on both sides. Eventually I reached a lighted crossroads, and sure enough one shop had a number: 15. (I hoped this was Western 15, or else I could be completely turned around.) After a good quarter of an hour of walking I found the place, had dinner (black ravioli with crabmeat, Perrier, all quite good despite being thoroughly unEgyptian: there wasn’t a single word in Arabic on the menu or the signage) and decided that on the way back I’d count the number of buildings there actually were between 22A and the beginning of the street. It wasn’t easy to be sure, because some of the vast, dark mansions might have housed one family or entire legions of the undead, but I reckoned 64.

Final thought: I like Arabic. My favorite script is Malayalam, which looks like a series of elaborately-bent paper clips, but Arabic is cursive as all get out and has a delightfully unpredictable peppering of dots, reminding me of the gleeful abandon with which my students decorate their work with apostrophes.

Many of you were kind enough to write to me saying how much you liked my two previous anecdotes from Egypt. Several more of you, or perhaps the same several, also said you’d like longer posts from me in future. So here, and for the next few Sundays, is the somewhat-more-complete story of my trip to Egypt. Or at least the parts you haven’t heard already. (The events of Saturday, July 26, both hilarious and depressing, are to be found in my earlier post, The Camel’s Ass.)

Many of you were kind enough to write to me saying how much you liked my two previous anecdotes from Egypt. Several more of you, or perhaps the same several, also said you’d like longer posts from me in future. So here, and for the next few Sundays, is the somewhat-more-complete story of my trip to Egypt. Or at least the parts you haven’t heard already. (The events of Saturday, July 26, both hilarious and depressing, are to be found in my earlier post, The Camel’s Ass.)

Sunday, July 27

Back to the Ministry of Half. This time I knew where to be dropped off by the taxi driver, which side of the building complex to approach, and I had Dr Amr Kandeel’s card to flash at the soldier at the locked front gates. When he took it and looked a little blank I realized that he probably couldn’t read English script, but the card did the trick and he duly unlocked the gate and let me in as if I were a visiting diplomat. Which, in a way, I was.

The Health Ministry, like many of the government buildings, had a feature once common in the U.K. but now very rare: iron railings, painted black. Very suitable, very much of a piece with the dignified style of the main building, with its columns and brilliant white façade—but during the Second World War those railings were sawn off, all over England, and melted down to make shells, bombs and tanks. Everywhere you go now, even at my old school in Worcester, you see the stone footing studded with short, square nubs, another wartime sacrifice.

The staff recognized me, grinned, bowed, ushered me in to see Amr Kandeel, the man in charge of combating infectious diseases in general and avian influenza in particular in Egypt. I was struck again by what an impressive figure he cut: tall, thoughtful, impassive, immaculately dressed, almost military in bearing.

He called in Dr Shermine Samir Aboubaker Aboualazem, or Shermine for short. She, too, was an impressive figure, fashionably dressed in a ruffled flowered blouse and lemon-lime jacket, black slacks, high-heeled sandals and gold jewellery, with her shades pushed up on top of her flowing hair, brown with highlights. Her nails were polished black with white cuticles. Her card said “Occupational medicine specialist,” but she was clearly an administrator of some clout: as she entered the operations room all four women working there stood up.

Her spoken English was good—as it should be for someone in charge of communication, at this level of government. She began by talking about surveillance of avian influenza, or AI. Every one of Egypt’s 26 governates (i.e. administrative regions) reports daily on AI, with all the usual details of names, place and date of admission, age, sex, exposure to poultry or not, possible symptoms, and whether two throat swabs had been taken. These forms are taken seriously, she said: if they’re not in by noon a call goes out from someone high enough in the Ministry to scare the pants off the provincial office—and sure enough, right before noon an assistant from the outer office wearing a black burka (though decorated with white and turquoise embroidery) came in with a sheaf of forms and began sliding them into the transparent pockets on the wall that were still empty.

The two throat swabs are tested in the lab in Cairo within 24 hours and, if positive, a blood test is used as follow-up. All the data are compiled and presented in a daily briefing for AK, the deputy minister and his excellency the minister. Any confirmed cases are sent at once to one of three dedicated AI hospitals in the Greater Cairo area, two for adults and one for children. Unlike the U.S., there’s no distinction between public and private healthcare: all are required to report, and the isolation facilities are in public hospitals.

I asked about traditional healers in rural areas: didn’t common folk go there first? In Pakistan and probably a lot of other countries I’ve researched, it’s alarming how many people ignore conventional medicine and even more alarming what absurd and potentially fatal treatments they submit to at the hands of the quack on the street corner. Shermine smiled. They had just finished a major survey to ask that question and found that in fact the primary healthcare setting is the first destination of choice. Well, well. If true, that’s remarkable and encouraging.

Egypt is clearly miles ahead of the US in education and outreach (a fact that would be even more apparent during the 2009 U.S. swine flu epidemic, during which the two most popular sources of information were gossip and hearsay). To date, she said, they’d run between 5,000 and 6,000 seminars on AI for professionals and for the public. Next month alone a single initiative would present AI seminars in 1,700 local clinics.

They’ve also worked a great deal on health, safety and behavior change. More than 5 million Egyptian families rely on poultry as a source of income, so an enormous effort had to go into changing old habits, practices and beliefs. The Health Ministry urged them (especially the women, as women traditional breed and raise the poultry, especially in the backyard home/farms) to uses masks, scarves, gloves or plastic bags on their hands, to use disinfectant, to wear different clothing while they working with the poultry.

“The results were amazing,” she said, talking avidly with hands and eyebrows. “More than 60% of the public changed their behavior regarding breeding.”

Another example. “Not long ago, you could see the chickens freely walk around, even in the house,” she said. “The breeders didn’t use cages. We had to teach them to keep the chickens in cages.

“It’s most difficult to fight the beliefs,” she went on. In the Arab world, she said, it’s traditional for the women to do the chicken-buying, and in doing so to squeeze and poke and examine the chicken close up, like a Frenchwoman buying fruit. Her department, she said, is working to try to minimize this laudable but potentially dangerous shopping style.

One set of crucial players have been the radaat rifiat, who in South Asia are politely called Lady Health Workers—trained health visitors who spend their time in the field, visiting homes. Egypt employs more than 13,000, who have made a total of more than 5 million home visits since the beginning of the crisis. (Didn’t see much of that kind of involvement during the U.S. swine flu epidemic, either.)

They also had to educate farmers about AI itself. Ducks, for example, can carry the virus while showing no symptoms. Ducks harbor every form of flu virus known. Ducks are airborne flu virus delivery systems.

She took me to the operations room, were a wall map showed speckled areas in the upper Nile, around Cairo, in the Delta, at the southern end of Sinai and at the head of the Red Sea. (Check) These are stopping-areas for migratory birds. The Ministry of the Environment, she said, carries out regular checks on birds in twenty or so migratory landing sites and shares its results with the Health Ministry and other agencies plus the WHO.

I asked to visit a backyard farm, to see ordinary people trying to cope with the problems of a potentially fatal infectious disease. She said she’d try to set it up.

In a delightful but unintended segue, I ate lunch at Kentucky Fried Chicken downtown, a fascinating experience in that I could have been on Oxford Street or Place de la Concorde or anywhere. Traffic outside, people inside from all walks of life, the young chirpy, assertive front-of-house girl seeing me, saying “Hi!” and going through all the fries-no-fries-Pepsi-no-Pepsi-spicy-or-mild options in English at top speed. She could just as easily have been an Egyptian recently arrived in London or New York. “Have a nice meal,” she said, and though part of me thought “corporate training,” part of me wanted to believe that she was sincere, and that she was as pleased to offer her English as I am to offer my three words of Arabic.

Spent the afternoon trying to walk back to Zamalek, succumbing to the heat, flagging down a taxi, arguing with him because he didn’t like the limp, dirty ten-pound note I’d got in my change at KFC, and then flaking out in my room with a cup of tea and a digestive biscuit. Travel is always a combination of excursion and retreat, the new and the familiar, and for every hour spent in 100-degree heat in an unfamiliar city we need the psychic equivalent of a digestive biscuit. Or a bath. Or even Italian first-division soccer.

Dinner at Dido’s, small, crowded, cheerful student pasta dive fifteen minutes’ walk toward the northern tip of Zamalek, with pretty decent food at remarkably good prices. Had a carbonara with fusilli made with beef instead of bacon—a small improvement in nutritional terms, a big one if you’re Muslim! As I was walking there I passed the Chinese Embassy, which had some pretty serious security and a few propaganda posters on the front walls—a marked change from the usual villa-plus-high-wall approach of most of the embassies here. It’s fascinating how Zamalek manages to have all these diplomatic buildings without having the hostile, defensive air of the wealthy districts of Karachi. Must be all these trees.

Monday, July 28

Slept well but woke with my throat so sore I can’t swallow or talk above a painful and pathetic croak.

This must have been something I picked up on my day-trip around the desert ruins, usually thought of as a hostile environment for viruses. This must be a local speciality—Camel Throat, perhaps, or Giza Gorge. Sarcophagus Strep. Ramses’ Revenge. West Nile Virus? Or given that I’m staying on an island, Mid-Nile Virus?

Sent emails to everyone cancelling my planned trips to the Chest Hospital and the Ministry of Half, and was surprised at what a relief those cancellations were. Sickness can in itself be a vacation, granting you the right to do exactly what you need to do exactly at that moment. I learned that on the island of Culebra, one of the Spanish Virgin Islands. I’m uneasy on standard vacations, bored and fidgetty, but that particular holiday changed completely on the fourth day when suddenly my daughter Maddy, then eight, suddenly fell sick and began throwing up. To anyone else that might have been a disaster–to me it was the best way I could possibly have spent the day, comforting her, holding a cool cloth to her forehead, telling (by her request) tales of adventures and misadventures from my own childhood. For once I could focus all my energy and attention on a single, worthwhile purpose, and that in itself was like being on holiday.

By the following day she was well enough to run around and even go snorkeling, but by then I’d come down with something myself, not vomiting but lying limp all day, watching tiny lizards make their way up the wall and across the ceiling, letting my mind take its own vacation, slipping easily between the real universe and the imagined one until there was no distinction, no time, no effort, no worry—the kind of travel we dream about.

In that sense, this day in Egypt was a day of travel, too. In fact, this all suggests that we need two kinds of travel—the travel that explores and the travel that processes and heals. The mind never stops traveling; it’s just that we try to give it different kinds of itinerary, some more enclosed and obsessive than others. Come to think of it, what we do with our minds goes back to that string-theory notion of an entire dimension being coiled up almost infinitely small. There are certainly times in my life I’ve sent my mind on fool’s errands like that.

This morning’s travel, then, consisted largely of reading books and daydreaming in the bath. (While drinking innumerable cups of tea.) In fact, I’ve been reading Jasper Fforde, who writes books about people traveling in books, and from book to book; he writes imaginative stories about imagination. In doing so, though, all he’s doing is creating imaginary structures within imaginary structures that are both metaphors and stimuli for the way the mind works on its own without the help of books at all. Any book offers a form of mental travel—but so does a bath and a cup of tea.

Which reminds me:

Yesterday evening, walking back from Dido’s, I saw a sizeable crowd on a side-road and went to investigate. Service had ended at a mosque, and probably a couple of hundred people, most of them very well dressed, were spilling out on the sidewalk and road.

Right ahead of me were two young Westerners, a boy and a girl, possibly from the American University of Cairo, which was nearby. The girl was blonde, and as I passed them she caught sight of me for an instant and then turned back to the young guy. I imagined that she and I had a conversation, which began when she asked me, not quite scornfully but certainly without a great deal of interest, what I had to offer that this young guy didn’t.

I chewed on this for a while, and reinterpreted the question slightly differently, as if she had asked, “What is your value?” or perhaps “What makes you interesting?”

“Well,” I said diffidently, “these days I’m working on trying to become wise.”

The idea struck her as odd, but she was curious enough to ask, a little dully, “How do you do that? Read lots of books?”

“I do some reading,” I said, aware that I really don’t read all that much but also aware that the Middle Ages notion of wisdom through constant scholarship doesn’t appeal to me, and moreover I don’t think it works. “I also do some writing, and I do a fair amount of travel.” Travel, it seemed to me, was a central part of my curriculum. “And I spend a lot of time thinking.”

That was it. The mental she lost interest in the mental me; or, in other words, the mental me lost interest in the mental her.

Wisdom doesn’t come just from reading, or just from experience, such as travel. (All experience is travel of a sort, as it involves a movement of some sort from where you were to somewhere new.) Wisdom also requires a willing slackening of the grip—the grip that resists change, the grip that wants to stick to the plan, the grip that assumes that we know something. One way of slackening that grip is by having plans break down, though that can be a bit brutal; another way of slackening the grip is by falling sick. So far this throat thing has been uncomfortable, even momentarily painful, but not what I’d call brutal. I’m grateful to it.

When my mother was in her last few weeks her mind seemed released: she told me stories of her childhood, of her first trip to New Zealand. She giggled like a schoolgirl. She was younger than she had been for decades. Wiser, too. So interesting that one moment we think of wisdom as consisting of a greater quantity of knowledge about this world, but then the next moment we think of it as having the ability to be both within this world and beyond it.

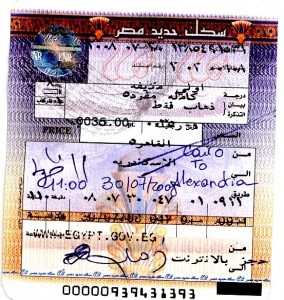

The manager, whom I think of as being named Dido (the Horus’s wi-fi password is didos2008), has brought me my train tickets to and from Alexandria. Maybe it’s my weakened state, but I see them as extraordinarily beautiful, the background printed in desert sunset colors, pink fading up to purple, and the Arabic writing dancing across like flocks of birds returning to roost. I have no idea what any of it means, and for the time being I have no intention of finding out.

Kassem, my contact at the WHO and the sweetest guy on Earth, heard that I wasn’t feeling well and emailed back:

I am ready to meet you anywhere and any time.

I am physician and it is my duty to take care of you.

Please send me your hotel address if you are not able to go around.

Kassem

Vulnerability is such a strong force. It’s like the physics of travel. Vulnerability elicits kindness, and kindness sets in motion that ineffable set of paired forces, generosity and gratitude, which orbit each other, each attracted by the other’s potent gravity, the energy of each reinforcing the energy of the other.

The second-sweetest guy is a short Egyptian with a weather-worn face and a small moustache who has been tidying my room. Worried that the room was too hot for me, a pallid Westerner, he asked, “Condition?”

No thanks, I said.

“Condition!” he urged. “Room hot!” He picked up the remote and turned on the a/c.

Later in the afternoon I got out the Voyage-Air (my folding guitar designed for the guitarist who is terrified of what will happen to any instrument consigned to the cargo hold, and is determined to take it into the cabin), unfolded it and asked the young desk clerk if it was okay to play in the lobby area. “We would love it,” he said in his stiff but oddly touching English.

I sat on a couch and played for maybe 20 minutes: “Someone to Watch Over Me,” “God Bless’ the Child”–songs that, unintentionally, reflect a kind of tenderness and protection. It calmed me, made me feel much more at home.

A couple of the guests said something complimentary as they passed, heading into the hotel or out, but I didn’t really care. When I was 20 I’d have wanted to be the center of attention, preferably women’s attention. Now I was perfectly happy playing to the desk clerk, the hotel staff. They grinned and nodded.

Dragged myself to dinner at Sabai Sabai, a Thai/Asian place seven or eight minutes’ walk away. Food was good except for the soup, which was outstanding. The walls were plastered in such a way as to give them a very odd color and texture, best described as taupe distressed stone. As a result it was, paradoxically, like being in a tomb, but a fun tomb. A party tomb. The chair backs were entirely covered in white cotton cloth wraps, adding to the sepulchral feel, yet the whole place managed to seem lively and convivial. Wherever possible, someone had put a Balinese dancing-girl picture, sculpture or doll. White parasols hanging in all the ceiling corners made it feel as if everyone was taking a break from a photo shoot for a remake of Mary Poppins aimed at the Japanese schoolgirl market.

Again I was reminded of the ability of techno music to penetrate any culture. Somewhere in London right now a music producer with a clipboard is turning to a guy programming a drum machine and saying, “Right, then. Next one’s number 225–the Papua New Guinea mix.”

All the same, having eaten at most of the best restaurants on Zamalek, I find myself wondering: Why don’t middle-class Egyptians eat Egyptian food? Or to put it another way, why is the Egyptian food in middle-level restaurants rather uninspiring? Is it like the Brits and British food in, say, 1973, when most pubs served nothing better than crisps and cardboard sandwiches, and if you had the cash you ate French or Italian? In other words, national cuisine is at best taken for granted and at worst sneered at? The tastiest Egyptian food I’ve ever had was in Boise, Idaho, at a restaurant called Aladdin’s, run by a former head chef at the U.N. in New York. That had a zest and an ambition that I’ve yet to see here. A bit sad, really.

Tuesday, July 29

Today’s agenda was to ignore my bout of Mid-Nile Virus (my tongue is a watery crimson from sucking so many Hall’s strawberry-flavored Vitamin C lozenges) and visit Ola Lawrence, the head of an agency called ENSTINET, whose job is to coordinate and promote Egyptian science and technology research.

Fascinating experience being driven to her office by her driver. He was the first Egyptian driver I’d been with so far who has shown any sign of impatience, honking not only in a “coming-up-on-your-left” way but also in a “why-don’t-the-five-of-you-get-your-act-together-and-clear-this-junction-before-we-all-die” sort of way.

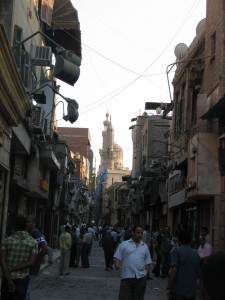

The ENSTINET building, which also houses several other ministries and government projects, was in the same general area as the Health Ministry—i.e. behind the Parliament building—but perhaps it was a sign of its junior status that rather than having a nice broad palatial frontage, like that of the Ministry of Half, we had to sneak up on it by doing another of these fascinating Egyptian dimensional strings, though this one proved the “handedness” concept of mathematics by requiring seventeen consecutive right-hand turns. Maybe there are dimensions and anti-dimensions, and this was the anti-dimension to all the left-handed corridors in the Horus Hotel.

Reinforcing this impression was the fact that with each right-angled turn, the road got narrower and narrower, or rather the drivable roadway got narrower and the number of pedestrians on the roadway began to outnumber the cars. After a while the actual width between the buildings on the left and the buildings on the right probably reached an irreducible minimum, but the number of ranks of cars parked on both sides continued to rise. At one point, in fact, we had to wait while a small boxy white Fiat reversed farther back into a driveway so a black BMW sedan could back into the space the Fiat had been created, and another black BMW drove toward us, coming the wrong way up a one-way street, and slotted into the space being created by the first BMW.

Just when I thought things couldn’t get any more crowded, my driver turned right and then pulled into the forecourt of a gas station that was doing double duty as a ministerial parking lot. A quick count showed sixty cars on the forecourt, two and three deep. The space was so tight that when it was time to leave my driver had to do not a three-point turn or a five-pint turn but an asterisk turn in order to get out. At some point, I sweat, that car plotted every diameter of the compass.

Ola Laurence was clear, decisive, middle-aged, dressed Western in paisley blouse and brown pants. Gold jewellery again. Her assistant was dressed more conservative Muslim again. I wonder if there’s an Islamic limit, a crescent ceiling—in other words, if you’re an orthodox or conservative Muslim you’re never likely to rise to the highest ranks–or whether it’s more that the most senior staff are simply more likely to meet Westerners and dress as such? (Later my colleague Omar, who knows both the Muslim and western worlds very well, told me that the phrase “crescent ceiling” is so apt I should patent it.)

Turns out she’s in charge of research, but also very focused on getting Egyptian scientific research seen and accepted by the broad world. Apparently there are something like 600 scientific journals published in Egypt but only half-a-dozen at most are internationally indexed. In other words, Egypt is scientifically and culturally a little isolated. She’s very keen on having Omar run workshops for the researchers on how to write a proposal and then write an article, and for the editors on how to raise the standard of their editing to global level. She also wants me to run a workshop on writing press releases and writing for the general public, and also wants to create an Egyptian TV program along the lines of the Discovery Channel. Apparently the channel is there already, but the content is not. I love being in at this stage of things: all kinds of scope for exciting and creative ideas.

Later, eating expensive Western pastries at Joffrey’s, the cafe by the Horus, I wondered about Egypt’s place in the world. Most moderately educated people here have a smattering of English (and gallons of goodwill), but what even the high-level scientists, doctors and administrators don’t have, it seems, is really advanced proficiency in English. Bangladesh and even Pakistan (and India, of course) seem to be streets ahead, linguistically. Why is that?

It seems to me that the South Asian countries made peace with their Anglo colonial history even as they were working to supercede it, and as a result they can continue to look to the Anglo West, whether to the U.K. or the U.S. Egypt overthrew the colonial yoke more recently—and in addition, I suspect that when Nasser threw in his lot (temporarily) with the Russians and then threw the Russians out with the idea of creating a pan-Arabic union, that Anglo heritage was thrown out with the bathwater.

Meanwhile, part of Egypt’s colonial allegiance is to France, further weakening the English-language connection. I feel sorry for Egypt: it strikes me as a proud but not arrogant nation, conscious of both its position as a cradle of civilization—the country that made Europe what it is today—and of its more recent trappings of European civilization reimported from Britain and France.

It’s not an African country, it’s not one of the poor Arabic desert states (which Egyptians, I suspect, see as uncivilized), it’s not one of the rich Arab desert states (which Egyptians, I suspect, see as vulgar) and, thank God, it’s not a puppet of the U.S. All in all, it must feel that it lacks allies while also lacking the economic/political/military clout to stand alone.

Spent the heat of the day resting up and watching Italian first-division soccer on television—a discovery that filled me with joy until I found out they air the same game several times during the week. Finally prised myself off the mattress to go out for another decent dinner at the Asian restaurant. My walk there and back took me past two or three embassies, a cluster of shops and some miscellaneous buildings of apparent (inexplicable) strategic importance, and en route I devised Brookes’s Law of Egyptian Weaponry: Nowhere in the world are more guns in the hands of people who seem less likely to use them.

There seem to be two types of armed security people, those in white uniforms and those in black. The whites, whom I take to be police, are everywhere; the blacks, whom I take to be soldiers, seem to be at more strategic targets, such as the Chinese embassy.

First of all, their white fatigues, which you’d think would be hard to keep clean, are spotless. Second, none of them are fat. Most are young, all are lean; none have the air of laziness or bullying or indeed the desire to intimidate by looking butch. Some carry handguns; most have what I take to be semi-automatic weapons or SLR’s. In a five-minute walk around Zamalek I’m like to see at least half-a-dozen lethal weapons. So what makes is seem so unlikely these guys will use them?

Well, for one thing, their stance or posture. I’ve yet to see anyone at attention, whether with weapon grounded, held or shouldered. Or in that classic pose of feet together, hands clasped behind their backs that even EMT’s imitate in the US. Their posture, in fact, can only be described as ordinary.

On the way back from dinner tonight I saw one pair standing in the road talking amiably to each other; one pair at their post (typically a small wooden sentry-box without equipment or furnishings but often with some graffiti) with one sitting and the other standing; one was sitting between two civilians checking a text message on his cell phone (as was the civilian next to him); one was sitting at some kind of gateway or entrance chatting to two civilians who were lounging with him; one was walking down the road carrying his shopping in a plastic grocery bag. Actually, I did see one guy with his hands clasped behind him, but that was just so he could lean back against a lamppost.

Their posture is anything but military—but on the other hand, it’s not the kind of extreme slouching or slovenliness one would characterize as unmilitary. They’re just ordinary. They look like the civilian gatekeepers or doormen at a hotel, shop or other building of substance: although these doormen are typically older and shorter, in posture they and the soldiers are pretty much identical. It’s the posture of people who have nothing specific to do at the moment.

Then there’s the way they react to the public. I tend to want to be on the same side as people with guns, so as I go around the city I often nod to these soldiers as I pass them. Almost all of them say a cheerful but casual, “Allo,” in the Egyptian Anglo/French way. Some grin. Nobody gives me the hard eye or the cold shoulder. Nobody gives me the brisk nod, the searching look up and down. It’s possible that the soldiers in black have been a little less forthcoming, but not so’s you’d notice right away. And as I’ve said, many of them are spending the time chatting to each other or to their civilian buddies. It’s pretty much only the uniform, and their general young leanness, that sets them apart.

Finally, there’s the way they handle their guns. I’ve tried to put my finger on exactly what it is about this, and it’s not easy.

They don’t handle their guns as if they were ordinary members of the public, because you and I would be self-conscious about having anything of that size and heft, especially anything potentially deadly, in our hands.

They don’t keep them at the ready, either. In Pakistan the soldiers, the army and even the armed gatekeepers hired by the wealthy seemed far more aware that they were holding a symbol of power, and that symbolism should be readily apparent to the casual glance. And police in the U.S.—sometimes the presentation of the sidearm seems to be the focal point of the way they carry their entire being.

No, here it’s as if the weapon is utterly familiar but largely unconsidered. I was going to write “unimportant,” but I don’t think that’s the case. It’s more like my black leather knapsack that I take everywhere: it’s very important to me, but it’s so familiar that it’s rarely a conscious act to carry it, or to shift it from shoulder to shoulder, or even to put it on the ground by my feet. Its meaning and presentation are almost internal, almost an extension of myself, like clothing, rather than about my relationship with the world; and that, apparently, is how the police in the white fatigues think of their guns. Every time I see them I, even as one who detests guns and am frightened of them, feel oddly comforted.

Wednesday July 30

Slept poorly because of my cold/Mid-Nile Virus thing. Looking very gaunt; skin falling off my face. But the promise of the new—in this case, a trip north, following the Nile, to the ancient port of Alexandria to meet potential colleagues at the University of Alexandria School of Public Health and the Library of Alexandria–bucked up my spirits. As soon as I got past the draining-my-sinuses-coughing-my-lungs-clear-taking-the-last-of-my-Tylenol-to-beat-back-my-headache stage, I started getting excited.

“Ramses train station,” I told the cab driver, who was short and weatherworn. “Ramsis!” he nodded eagerly, and for a few minutes I was hoping he didn’t think I meant the Rameses Hilton, like a vast fat pillar to commerce and cable TV on the Cairo side of the 6th of October Bridge. But no: we tooled past the Ramses Hilton in the middle lane.

In true Egyptian trafficological fashion, we also sailed past the railway station, but I wasn’t fooled: in Egypt, as in South Asia, when there’s a divided highway, rather than do anything that would force the general circulation to stop for even an instant and require obedience to traffic directions, the city planners (I use the phrase hypothetically) always look for a merge solution. Sure enough, we went probably three-quarters of a mile past the station on the right lane of the divided highway before reaching a U-turn cutoff on our left, whereupon we and dozens of other cars swung left and nuzzled our way into the oncoming traffic, and drove the three-quarters of a mile back to the station.

It’s very interesting, now I come to think of it: the main motivation, I suppose, is to save money building some kind of space-intensive and complex interchange system of the kind you see at airports, in particular; but the effect is that drivers are faced with the human and immediate obligations of dealing close up with other drivers, so a literally face-to-face series of encounters is what govern that complicated human intercourse we call traffic. (In German “traffic” is verkehr, which also means intercourse in the sexual sense.) In the West we look to obey more abstract orders: lights, road signs, evidence of collaborative acts of civic planning and government. Here there’s much more of a sense that everything significant in the moment-by-moment process of living is going to be resolved by those immediately involved.