I am in Bangladesh for many reasons, one of which is to test a strange, doomy hypothesis.

As global warming melts the polar ice cap, that moisture has to go somewhere. Some of it causes the oceans to rise, or in our local case Lake Champlain, which set new records for flood levels and then refused to go back down. Much of it, though, falls as rain or hangs in the air as water vapor. Some say the world will end in fire, Frost wrote, and some in ice. My hypothesis is that it will end in rain. It’s not the temperature that will be the end of us; as they say in Florida, it’s the humidity.

Or to give this situation a more imaginable form, think of the landscape of Blade Runner: the world as one great collapsing city, under endless rain.

Where better to study what this will look like, then, than in a country that, according to WeatherUnderground, was currently experiencing temperatures of 85-90 but humidity of 85-90 percent?

So, off to New York, then Dubai, then Dhaka.

Dhaka airport itself was invisible under low cloud: the runway appeared only second before the wheels touched it. In the jet bridge, the air reminded me of flying into Belize City. I can manage this, I thought.

I had worked up a sweat long before I left the airport. Baggage from our flight was unloaded randomly onto several different baggage carousels, and a couple of hundred bewildered people pushed their overladen carts from one to another, peering first at one belt, then another.

The flight had landed 45 minutes late, and by the time I retrieved my bags and headed toward the crush outside the arrivals area, I was starting to be a little concerned that my driver had up and left. No small white sign with my name inside baggage claims; no sign among the first public throng. Then I pushed open the front terminal doors, and the world vanished.

It vanished, of course, because even the hot air inside, with its added hints of sweat, belt rubber and exhaustion, had been to some extent conditioned. The real air, outside, smacked against my glasses and clung on in grateful watery globulets. I couldn’t see a damn thing.

I took my glasses off and the world reappeared, but even hazier than usual. The middle and longer distances seemed to have vanished. Closer at hand, a dozen Bangladeshis were crowding around me asking, “Taxi? Taxi? Do you need help, sir?” Beyond them I could make out the usual half-dozen slender young soldiers making vague and unthreatening waving gestures that were routinely ignored by everyone, and beyond them the curb, where half a dozen taxis and minicabs were packing in new arrivals in another form of supersaturation. But the rest of the region—well, it consisted entirely of water.

Let me try to be more precise. It was raining, but the rain had a quality I’d never known before. It didn’t seem to be coming down, or blowing sideways: it seemed to be emerging from invisible pores in the air itself. The air, in other words, was sweating. Of course, the ground was also wet, the tarmac out in the open a series of silvery greys, the tarmac under the airport frontage a series of darker greys, but all were unified in a way that the meteorologists dub “Humidity, 104%.”

I looked down at the directions in my hand, which purported to tell me where I’d find my driver. They seemed to have been drawn both not to scale and not to direction, an unusual combination. Worse, the paper, though not yet exposed to rain, had already started wilting, and began to droop from my hand. Given that I was already trying to carry my knapsack, my traveling guitar, my suitcase and my glasses, this droopage presented a major problem. I had to bend forward and try to read the map upside down.

As far as I could tell, the instructions told me to turn left. I shuffled off leftwards, dragging my baggage and a small percentage of the private transportation employee population of Dhaka, through the first of two security checks (where, following local custom, I was nearly run over by several cars and a minibus) and into another identical concourse exit, where my current batch of taxi-drivers gave up and was replaced by a fresh batch.

“Go through two security checks,” the upside-down instructions said, so once again I moved crabwise past cabs, indolent soldiers, near death, and so on, and at this point found myself outside.

“Outside” meant “no longer under any overhead protection, so in theory I was now being rained on, but to my surprise not much changed. My shirt was already sodden. My socks were already sodden. My instructions were already hanging limp in my hand like a wet handkerchief. The open tarmac around and in front of me was still a series of opaque greys and silvers, merging into a complete opacity as if the future itself were out there and consisted of nothing but water and water vapor.

The indoor taxi-drivers retreated back under what I will laughingly call cover and were replaced by their outdoor brethren, who instantly turned out to be much more helpful.

“Taxi?” they asked.

“Driver,” I replied, shaking my head.

They were, sensibly, not convinced. If I had a driver, why was I standing in the rain with all my bags trying to read a wet handkerchief upside down?

“Call him on your cell phone?” they suggested.

I was hesitating to do this for three reasons. One was that the driver’s number was in very small print hanging upside down, and I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to find it or read it. The second was that, if I had understood AT&T’s instructions correctly, would have to carry out a complicated procedure that involved dialing the United Sates, then the international code, then the Bangladesh country code, then Archimedes’ constant, Feigenbaum’s constant and the Gauss-Kuzmin-Wirsing constant and finally the driver’s social security number. But the most important cause for hesitation was reason number three, which was that as soon as I took my iPhone out of its little padded pouch its innards would immediately achieve 104% humidity and it would never work again, except perhaps in the shower, or an aquarium.

Luckily, one word of my now nearly illegible instructions was an capitals. LEFT, it said. Some kind of ramp led away to the left, and though it seemed to lead into the kind of parking structure in which Bangladeshi gangsters drowned their rivals, I could dimply see a small knot of locals waiting at the end of said ramp, one of whom looked as if (remember, my glasses are dangling from the little finger of my right hand, my only spare loading digit) he was holding a white sign.

And sure enough, this was my driver. He greeted me with the combination of enthusiasm and respect that never fails to fill me with sodden gratitude, placed my bags in the trunk, and peeled out of the gangster drowning structure and into the city.

The road to the city, which I remember from my last trip five years previously, was the usual constant merge of high-speed cars, slow colorful bicycle rickshaws and buses that had been so frequently battered they looked like shoeboxes wrapped in blue duct tape. Visibility was nil to the minus nilth. Everyone operated by echolocation—that is, everyone sounded their horns or bike bells constantly, the blind leading the deaf.

Once into the city proper, the landscape became even more amazing. Every street was awash. And I know my awashes, let me tell you: before I left, Burlington suffered a series of thunderstorms so heavy that I photographed someone kayaking up my street. But this was a different kind of awash. Water seemed to have created and defined the very contours of the roads, so in many of the side streets (and, by western standards, Dhaka is mostly side streets) the bicycle rickshaws in particular had to weave from one side of the street to the other just to be able to find solid ground. We passed an area in central Bangladesh that is a lake even in the driest of seasons, where people were commuting from the roadside to the shanty-town on the far side in a series of antique hand-paddled barge-canoes, like the principal Thames transportation in Shakespeare’s London. It seemed only a matter of time before cars would become obsolete altogether, and everyone would be rowing.

As we sloshed around something that must have been another street corner, I finally made a connection: no wonder the main institution I’ve been dealing with is called the International Center for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh. No wonder one of the country’s main concerns is water-born disease. At that moment, water could have born any disease anywhere. I coughed, and felt a strange sensation in my lungs: some furry fungal disease, its humid hour come round at last, had swum its way into my airways and was setting up for business.

Google Maps and Brain Masala

I have no idea what day it is. I suspect Sunday. Locally, everyone knows it as the day of hartal (which seems to be a combination of strike and, if everything comes together, a demonstration), and therefore a holiday. Apparently, one group has declared a half-day hartal, another a full-day hartal, and a full-day hartal trumps a half-day hartal, so a full day it is. In practice, this means, as Haroun at the guest house says, it is a holday, and the shops are shut. Certainly, the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR), where I’m supposed to meet my medical friends, is shut, and I have nothing to do.

Today is not actually raining, as far as I can tell, but everything (myself included) is slick with moisture. I’ve made two excursions, stepping carefully among the puddles and the acreage of mud, and heaps of bricks and dogs and small children who look up to grin mischievously and call out “Hello!” over and over. As soon as I get back to the guest house, I peel off my shirt.

My reconnaissance so far has taught me:

I am on Gulshan Road 12. Gulshan is, as one of the students from ICDDR,B called it, “the posh district,” which means we have mud and bricks and half-finished buildings, but we also have established residences with gates and slim figures in pseudo-military uniforms and paved courtyards with new cars and the usual rash of single-building academic centers, some of which are quite genuine, some of which (such as the one advertising all manner of courses and degrees and announcing its website, www.theprinceton.edu), are probably less so.

My reconnaissance notes:

L outside the gate, then R: Catalina Island Restaurant, Bookshop.

R outside the gate, then L to Sunny Dale Apartments, then L: road of rickshaws. At the end, turn R past series of one-car-garage shops, cobblers squatting on the pavement, leads to major chaotic intersection I shall call Piccadilly Circus.

On an insane whim, knowing that I should probably be doing some kind of reading or editing, I decide to Google Map the city of Dhaka.

This really flies in the fact of experience and common sense. When I was following the polio eradication program in Karachi, I discovered that Karachi, like many cities in South Asia, has no reliable street maps. (Nor census, nor most other items of informational infrastructure.) When we went off in search of a meeting at the Town Health Office, or even in search of the WHO headquarters, the driver would head off in roughly the right direction and then repeatedly ask passers-by if they knew where the THO or the WHO was. No street names. No building numbers. Barely any street, in some places. And even the locals didn’t know their locality: we spent 45 minutes within half a mile of the WHO headquarters, asking if anyone knew where it was, before we found it.

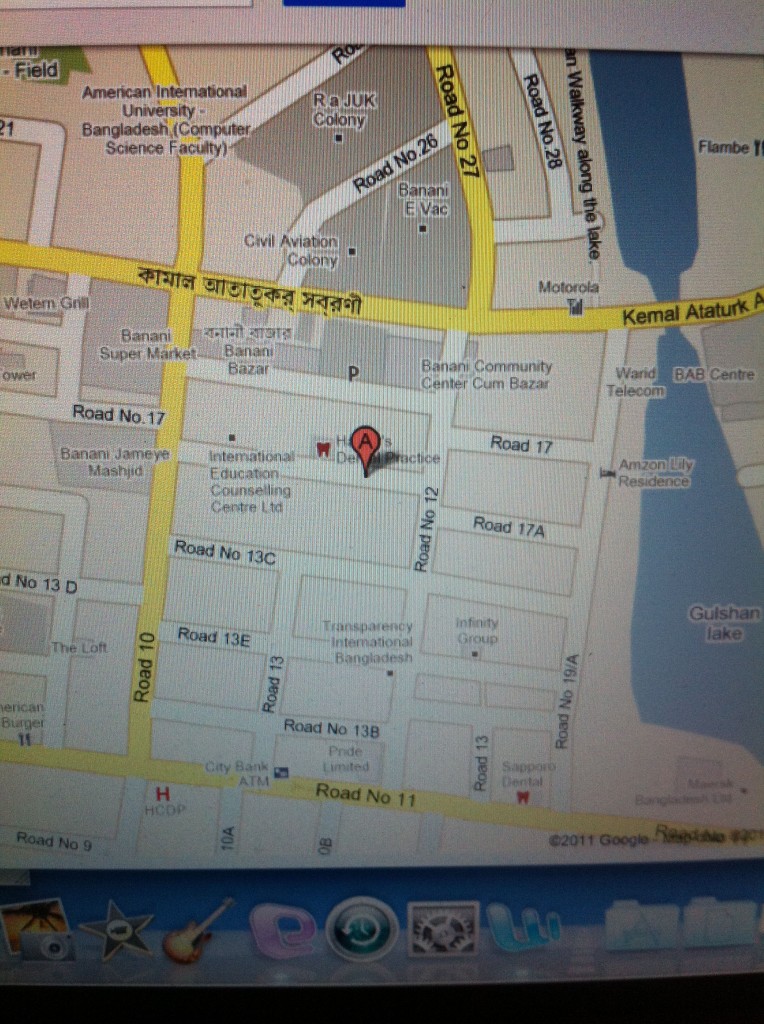

Incredibly, typing “Gulshan, Dhaka, Bangladesh” into Google Maps actually delivers what looks like an authentic street map. Having long ago learned that the map is not the territory and the Internet is not the map, I zoom in with cautious fascination.

What I find has that wonderful combination of plausible fact and plausible fiction. Road No 12 is indeed shown, though on the Google Map it is a clear, purposeful, finished corridor rather than a combination of construction and collapse amid mud puddles, laborers and small children. A number of local landmarks are spelled out, ranging from the impeccable (Transparency International Bangladesh) through the possibly dubious (International Educational Counselling Centre, Inc, which might be entirely genuine, entirely bogus or just trying to make a living any way it can), the mysterious (Amazon Lily Residence) to the delightfully vernacular (Banani Community Centre Cum Bazaar).

I love maps, and I love navigating by maps, but this map leaves me completely adrift for the simple reason that I have not yet seen, and may never on this trip see, the sun. Everything is cloud, sans direction. Normally, I can tell you at once, even if I’m indoors, which way is north, south, east or home. Here, I have no clue.

(Google Earth, by the way, simply backs up Google Maps, like mid-level executives covering each other’s asses.)

Consequently, I have no idea if the Catalina Island Restaurant is on Road No. 11 or on the curiously-named Kemal Ataturk Ave. (Why is the great Ataturk commemorated in Dhaka?) Haroun, giving directions from the front desk of the guest house, refers simply to “main road,” and I’ll bet a thousand taka that if I stepped outside the guest house compound and ask the first passer-by for Kemal Ataturk Avenue he’d have no idea. The map is not the territory, and the internet is not, whatever it may look like, the map.

Above all, anyone who uses an onboard GPS navigation system or an online map finds out sooner or later that the information is only as good as its human on-the-ground updaters. How often do the guys working for the mappers head out here, their clipboards floppy with damp paper, their shirts sticking to the fabric of their car seats? Can’t see it, myself.

Finally, in search of lunch, I’m forced to do some on-the-ground exploring: Road 12 actually runs between Road 7, home of the Catalina Island Bistro (of which more in a moment) and Road 9. Google Maps includes both 7 and 9 but in the wrong place and without a 12 running between them. Piccadilly Circus is in fact Gulshan (Roundabout Number) 1, not identified on Google Maps.

Mushtuq, the Principal Scientific Officer at IEDCR, explains the snag. At some time in the cartographic past, perhaps as much as 20 years ago, all the road numbers in Gulshan were changed. For a while, in fact, people’s addresses literally ran “House #12, Road #8 (old Road # 2).”

I was right: it was hard enough to get the GPS team to seethe in the traffic and slosh through the mud around here just once. To get them to come back and update was just too much. The map has been made: long live the map. Anything wrong with it must be the fault of reality.

As it’s the only place I know to have lunch, I walked around the corner to the Catalina Island Breakfast Bistro and Barbecue, featuring Live Entertainment.

In this part of the world, the rural idyll, the exotic getaway, is a popular concept in even the most unlikely settings. Stepping gingerly around a mud puddle on what I now knew to be Road 7, I crossing the faux footbridge over the faux lagoon, passed the concrete wall painted with the faux blue waves, and found myself the only customer inside a largely featureless interior. As in most places in the developing world, underemployment is a fact of life, and four people showed me to my table.

As usual, the western-style dishes were expensive, and as usual I wasn’t interested in them anyway. Stepping gingerly around the brain masala, I opted for chicken masala, palak paneer and butter naan, with a side of mango juice.

These dishes are familiar, by the way, because what I grew up in the U.K. thinking of as Indian food is in fact Bengali food.

Service was leisurely, and as I waited for my meal I realized that the bookshop next door (where I had just bought Lands of Glass by Alessandro Baricco, its cover already curling up from the damp, and Davd Mitchell’s The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, prudently hand-wrapped in transparent plastic) had as much custom as the restaurant—rarely a good sign for a restaurant. A waiter went out to sweep the Astroturf bridge with his whisk broom, and as he did so I saw to my surprise that the faux lagoon actually had fish. Their darting this way and that, and the wind flirting with the leaves of the palm trees and ferns, were today’s live entertainment.

The mango juice arrived, complete with both pulp and froth from the juicer. It was neither heavy nor sticky, and I remembered that monsoon season is also mango season.

Several people brought me clean plates, and my lunch, forking the naan onto a side plate, spooning up my chicken and paneer.

One bite—best naan ever. Fluffy, not greasy.

The chicken seemed to have been cut along Eastern rather than Western geometries, each bite featuring rather more bone and rather less meat that I expected, but all the same it was delicious, with just enough kick from the cardamom, and the palak paneer was the star of the table, with perfectly crispy chunk of fried cheese in a sauce that was colored by spinach but not overwhelmed by it. The whole meal came to just over 1,000 taka.

All morning my head had been congested. I walked back to Road 12 with my sinuses running wild and free.

Art and Smuggling

Of all the things I expected to do in Bangladesh (watching cricket, eating wonderfully spicy Bengali food, sweating through four shirts a day) something that didn’t make it on the list was being surrounded by Bangladeshi art. In fact, I hadn’t the slightest interest in or conception of Bangladeshi art. Well, I’m not alone: it turns out that Bangladeshis don’t know much (or, apparently, care much) about their own art, either.

Or so I was told last night during a wonderful, if slightly off-balance, evening at the home of the painter Fareha Zeba, her husband the sculptor Saidul Haque Juise and the eminent art historian Professor Enamul Haque, former director-general of the National Museum and Minister of Culture.

The evening was off-balance not because of the company, nor even because of the extraordinary range of original and collected artwork that turned every wall into a kind of concerto of visual activity. No, this was the evening before the notorious two-day general strike or hartal, which was busy throwing everything and everyone off balance even before it started. For one thing, the traffic, always…um…intense, was virtually at a standstill as some people tried to stock up ahead of the shop-closings, while others got ready to leave the city for what, with the Muslim weekend of Friday and Saturday and then two more days of hartal immediately afterwards, amounts to a six-day weekend. The strikers were adding to everyone’s nervousness by getting a kind of Cabbage Night jump on today’s strike by reportedly setting on fire eight buses, two private cars and a covered van, just to show they’re serious.

(I say “reportedly” because I saw no such thing, and having been in these situations before I know how vigorously rumor fans imaginary flames.)

So a seven o’clock dinner was pushed back and back as everyone’s trips home were held up, and it was after nine before my friend’s driver turned up at the guest house where I’m staying. I hopped in, half-expecting the worst, but the rumors had done their job: Dhaka, which normally has more traffic on any given street in one day than the whole of Burlington, Vermont sees in a year, was almost deserted. The dark, leafy streets felt eerie, and for the first time I thought we might actually move fast enough that I’d need to put on my seat belt.

It hadn’t actually rained during the day (thanks to all of you who emailed me to ask if the weather was still as saturated as it was when I landed) but it was still humid enough that when I got out of the car my glasses fogged up with a tenacity beyond ordinary shirt-polishing, so I was standing like a fool with my specs in hand when the door opened and I was ushered into a home that I can convey only by embedding a dozen photos or more into what follows.

Fareha Zeba’s paintings, some in acrylics, some in watercolor, had a kind of sketchbook spontaneity to them and more than a hint of magical realism: it was as if the guests were surrounded by another set of guests, the spirits of Frida Kahlo and dozens of other long-lost friends.

These faces, though, were only the most conventional of those looking out from the walls and past the guests. Saidul Haque Juise makes masks. He started out making what might be called life-sized festival masks, crisp and colorful with a certain birdlike quality, but then he began using local sands, rust-colored and gray-green, creating a basic structure and then painting it with glue and paint before sprinkling the sand on top. The results were amazing, timeless and simultaneously somber and humorous.

And all the other walls were covered with all kinds of other pieces of folk art: more masks, more faces, birds, animals, gargoyles.

The whole wallscape left me feeling exhilarated but pretty stupid. How come I’d never seen or even heard of exhibitions of Bangladeshi art? Professor Enamul Haque cleared things up for me. Of course there is Bangladeshi art, from contemporary to seriously ancient, but Bangladeshis have spent most of their history pretty much ignoring it. Not a single college or university, he said, offers courses in Bangladeshi art.

This reminded me of a conversation I’d had with a very bright young tour guide in Egypt. Egyptians have no interest in their own history, he told me. I was flabbergasted. What country has a longer and more colorful history than Egypt, much of it still visible from miles away? No, he said, he wasn’t taught anything about Egyptian history in school; what little he knew what what he had picked up in his training as a tour guide. The reason why Egyptians in general are so well-disposed toward the English and the French, he said, was that it was the foreign archaeologists who not only unearthed Egypt’s art and history but declared it to be of value. Even today the vast majority of Egyptian art a visitor sees is either (a) 3,000 years old or (b) tourist crap. It’s like Egyptian food: I spent weeks in Egypt looking for good Egyptian food, but Egyptians who like to eat go out for French, or Italian, or Thai. It’s a kind of national self-diminishment I found quite dismaying.

Back in Bangladesh, meanwhile, a different dismaying trend has begun: Bangladeshi art has at last come to be valued–by smugglers. Even though in theory it’s illegal to traffic in, say, thousand-year-old stone icons, the trade is as lively as the African trade in ivory or rhinoceros horn. By far the top destination, he said, is the United States.

Even at his advanced age, Professor Haque has started a project that, he hopes, may help to slow this grim art-drain. Deciding that trying to enlist the help of politicians or academics was a waste of time, he chose a remote region in the north of the country a recruited–children. About 180 of them, in fact, all pledged to respect and preserve their country’s history and artistic heritage by reporting any trade they saw taking place in their immediate vicinity in icons, statues, sculptures, paintings, figurines. A kind of Neighborhood Art Watch.

It’s early days, but he believes his Baker Street Art Irregulars are having a significant effect. He hopes to set up similar projects in other areas of the country.

It’s early days, but he believes his Baker Street Art Irregulars are having a significant effect. He hopes to set up similar projects in other areas of the country.

And then it was time to leave, before the hartal proper got going at midnight. I said my goodbyes and headed back to the guest house, my mind full of faces.

In Search of Endangered Alphabets

As alert readers of this blog know, I’m in Bangladesh in search of an endangered alphabet. To be specific, any one of the scripts used by one of the indigenous peoples living in the Chittagong Hill Tracts in south-eastern Bangladesh, over toward the border with Myanmar.

Straight away, it’s only fair to say that I’ve massively underestimated how hard this field work is. All over the world, anthropologists and field linguists are smiling grimly. Yeah, we knew all along.

So here’s a brief rundown. First of all, the combination of the monsoon and the political/security situation–until recently there was virtual civil war in the area–makes it very hard for me to visit the Chittagong Hill Tracts, and the hartals have made it all but impossible for me even to visit Chittagong city. So it’s a question of who is in Dhaka, or who is willing to come to Dhaka.

Several people in Bangladesh and elsewhere suggested my best bet was to meet one of the Mro people, and sure enough I was able to gather several possible contacts.

It doesn’t help that the Mro, as a marginalized people, are not wealthy, so they can’t gad about at the whim of an amateur linguist—who is pretty much unable to gad about himself, as the hartals have shut down almost all forms of public transport, and I can’t get a car and driver from any of my host institutions because they won’t put a foreign visitor in jeopardy.

(By the way, I thought this jeopardy business was exaggerated as usual, and I was told that the main centers of demonstration activity weren’t around me anyway—but this morning’s paper showed graphic photos of the Opposition Chief Whip being knuckled hard by police yesterday morning, and parked right outside the guest house yesterday I was slightly alarmed to see not only a police van but a TV news truck. They were expecting something.)

Of the list of contacts I had built up over the past few weeks, one by one (or in one case, two by two) they were melting away. One was off to Singapore, others were out of town, three were simply MIA, perhaps having thought better of my scheme. And a strange non-replacement scheme was taking place: each day someone would hear of my project, their eyes would light up, and they say they knew someone who cold help—and in every case these phantom contacts, too, would turn to vapor.

But the true depth of my naivete was revealed only when I started getting close to actually meeting an actual Mro.

Utpal Khisa, the most consistently helpful man in the country, put me in touch with Mr Ranglai Mro, and I had high hopes—but then it turned out Ranglai was actually back in the CHT. Once I braved the Bangladeshi phone system, though, he gave me the phone number of Kham Lai Mro, though, and Kham Lai unhesitatingly said yes.

But what exactly was he agreeing to? It turned out that he was in town for just a few days, staying at a hotel all the way across Dhaka, which is like saying all the way across Los Angeles. (Actually, to my nervous visitor’s eye, all the way across the Los Angeles of Blade Runner.) He asked if I could meet him. Of course I wanted to meet him, but there were no taxis, no buses, no available private cars, and it was out of rickshaw range. (There was a brief suggestion that I might hire an ambulance, as ambulances are usually safe during hartals, but no ambulances were available.)

Could he come to me, I asked timidly. I’d cover the cost of his transport. Yes, he said again, decisively. He would come to me at 10 the next morning.

Got up early. Opened up the right pages on my laptop so I could show him examples of what I’m doing. Set aside a fresh, unopened bottle of water, pretty much all I had to offer by way of hospitality. Got out a legal pad for him to write on.

10 came and went. I called him; he was taking care of errands, and could I call him in half an hour. I gave him an hour and called again. He could come in the afternoon. Wonderful. Did he know where I was?

By now it was becoming clear that we had, surprise, surprise, a bit of a language barrier. When he used mainstream English words, I was pretty much with him despite his strong accent, but anything Bengali, such as a street or district name left me groping. “Is there Bengali man in guest house with you?” he asked sensibly, and we added a translator to the negotiations—Mohammed Abdul Wadud, the guest house manager. Wadud did sterling work, and after Kham Lai tried again to get me to come to him, which Wadud firmly discouraged, it was agreed that Kham Lai would come to me at around 4.

With an hour or so to go, the sky opened and we had a brief but vigorous monsoon shower, which is all it took to turn the road into a shallow river of mud. And I was asking poor Kham Lai to make his way all across Dhaka in this.

The delay, as it turned out, was a blessing, because at long, long last it struck me: I was asking someone of uncertain education who spoke English as a third language at best, to understand and write poetry. What the hell was I thinking? If I could barely communicate map directions and times with him, how could I convey the complexities of script loss?

Brainwave: went downstairs, found Wadud in his office, and implored him to take my little poem and translate it into Bengali. Then Kham Lai could work from that.

Even someone as educated and multilingual as Wadud blinked and hesitated. This writing business is harder than I give it credit for.

He recovered, agreed a little uncertainly and asked if he might have a few minutes to work on it. I agreed with guilty unease, as if I were a pal of T.S. Eliot’s who has asked him to write, say, the Four Quartets, and would he mind getting a move on as I had a train to catch?

A quarter of an hour later, when I was on the brink of assuming that I was completely out of my depth and should leave all this to real anthropologists with some actual, uh, training, Wadud tapped on my door and showed me his work, a printout in Bengali font so crisp and beautiful I wanted to frame it. He walked me through the script, explaining that he had produced a second version with the word “then” added at the beginning of the last line to make it flow better. It was my Rosetta Stone.

No sooner had he retreated shyly from my room when my phone rang. “Your visitor is here, sir,” said the desk man.

In a state that can only be described as a tizzy, I grabbed legal pad, laptop, glasses, room key, two pens, two bottles of water, my phone and my wallet, and tumbled downstairs.

Kham Lai Mro turned out to be a short, handsome man of about thirty-five in alligator polo shirt and khaki pants. He also turned out not to be alone: his friend, in white short-sleeved shirt, jeans and sandals, was clearly ethnically different from Kham Lai, just as Kham Lai was different from your Dhakan on the street.

Sure enough, once we had settled in the lounge upstairs, Kham Lai drew breath and gave a practiced explanation of the indigenous peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. As a Mro, he was one of perhaps 75,000, the fourth largest of the ethnic communities; his friend was Marma. Each of the indigenous peoples had their own language, he said: it struck me as remarkable that there was such genetic and linguistic diversity within a relatively small area. Must find out how that came about.

He already understood the importance of one’s own native script. Five of the communities, he said, had their own scripts—he used the word—and could express everything that was important to them. When I showed him my poem in Bengali, with its text stressing the importance of one’s own written language, he read it and nodded approvingly.

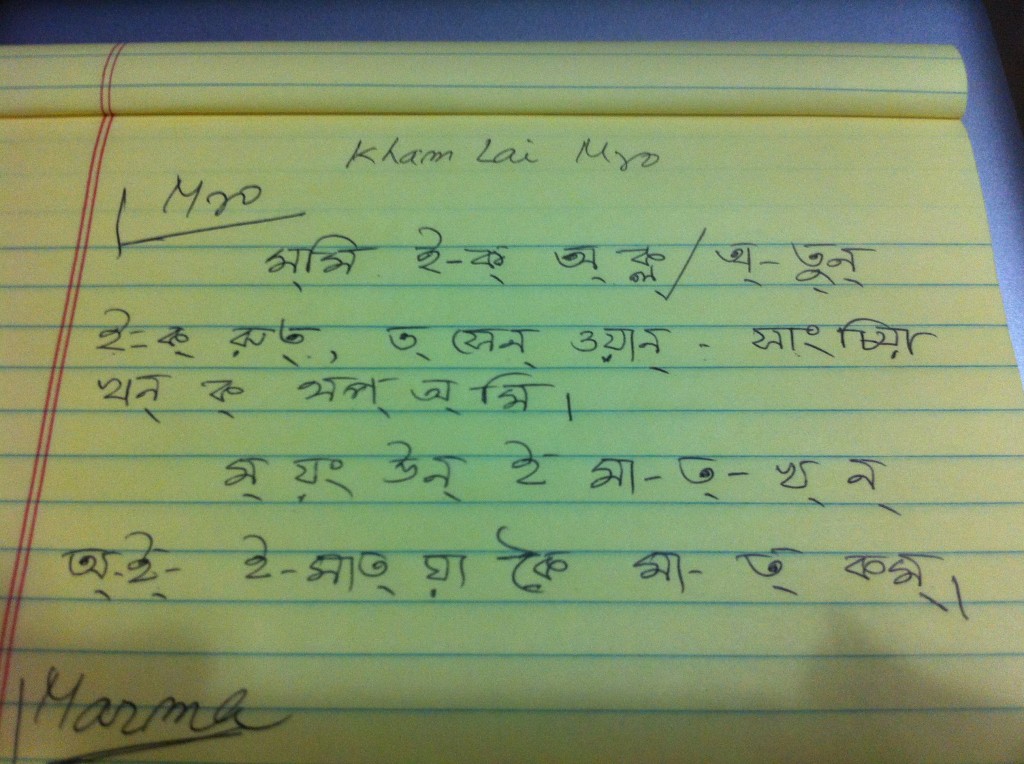

He gave a succinct, articulate and remarkably restrained account of the government’s attitude toward and treatment of indigenous peoples of the CHT area (news articles on the subject can readily be found online, as can details of Amnesty International’s involvement) and then I pulled out my legal pad and Wadud’s translation, and asked him to try writing my little poem in Mro.

“Of course,” he said graciously, leaned forward and concentrated.

For the first time in two and a half years working on this project, I watched someone actually writing in an endangered alphabet. He wrote firmly and fluently, pausing to make sure he had correctly translated each word, even offering me two alternatives for one particular phrase. In some respects the characters resembled a Devanagari script, with their superscribed line, but in other respects it seemed its own species, replete with diacriticals above, below and even between letters. I was already imagining myself carving it, wishing I had the same springy élan with the gouge that he had with the ballpoint.

I thought my geeky excitement couldn’t be much greater, but then he explained that his friend was Marma, and thus had his own language and script, distinct from Mro. I couldn’t believe it. I had hoped beyond hope for one endangered alphabet, and I had been granted two.

They worked together, Kham Lai writing and his friend correcting a word or a pen-stroke here and there. In other words, Kham Lai spoke not only Bengali, English and Mro, he also knew Marma and probably more of the CHT languages. No wonder he seemed to be acting as a representative of the entire hilly district.

Once again, Marma was familiar yet unfamiliar, sharing sme characters with Mro but using others of its own.

When they had finished and checked their work diligently, Kham Lai surprised me all over again by asking if I knew the work of the anthropologist Lawrence Lofler. (Or possibly Laurence Loeffler—I haven’t yet been able to track him down.) “He stayed in my grandfather’s village for five years,” he said. “He wrote a book called The Mro.”

I realized I still didn’t know the other man’s name, and, given my tin ear for local accents, might still not know it if he told me. On my request, he carefully wrote his name beneath his sample of Marma, in a curly and loopy Latin script, like roast beef flavored with Bengali spices: Chasa Thowai Marma, of Thanchi district, Bandarban.

Our time was up: they had a long journey home ahead of them. We said our goodbyes and they walked out, side by side, into the monsoon downpour.

P.S. AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAARRRRRRRGGGGGGHHHHHHHH! And other cries of despair and frustration.

Okay, I am getting the full anthro experience now–namely, I’ve just been told that everything I believed was wrong, and all the work I’ve done has turned out to be next to worthless.

Just met Shantimoy Chakma (like the Mro and the Marma people, the Chakma use their community name as their last name), a wonderful guy who is working on adapting Sesame Street for Bangladesh television. That in itself is a fascinating exercise in preserving and reviving traditional cultural modes, including scripts, among the young, but that’s another story.

He took one look at my legal pad and told me that yes, Kham Lai and Chasa had translated my poem into Mro and Marma respectively, but they had written it in the Bengali script. It looked sort of familiar to me, but then I’m not used to seeing handwritten Bengali and in any case they added their own dialectical diacriticals, so to speak. But the bottom line is–the Mro and Marma scripts look nothing like Bengali.

Shantimoy had brought with him a history of the Chittagong Hill Tract peoples and their scripts–a history he knows all too well, as his father was a noted writer in the traditional Chakma script, but during the fighting in that region their house was burned down twice, all his works were lost, and Shantimoy and his siblings grew up speaking Chakma but unable to read or write it.

All may not be lost, though. He has taken my poem in Bengali, once more approving of its sentiments, and promised to find someone who can write it in Chakma–and, with luck, another friend who can do the same with Marma.

All I can say is, it’s just as well I hadn’t already started carving.

Beyond Blade Runner

The other evening, as I was heading out through the upper-middle-class residential district of Gulshan to dinner with friends, I quipped, “Every road in Gulshan comes with its own pile of sand.”

The other evening, as I was heading out through the upper-middle-class residential district of Gulshan to dinner with friends, I quipped, “Every road in Gulshan comes with its own pile of sand.”

Actually, sand is just the start of it. Road 12, the road I’m staying on, in what would in most capital cities be the embassy district, is maybe a hundred yards long but currently has three separate piles of bricks, a large stack of bags of cement, two separate piles of demolition rubble, several stacks of concrete slabs and a variety of other assemblages that might be symptoms of either creation or destruction. That evening, as we were returning through the uneven, unlit streets around midnight, our driver nearly impaled the car on a bundle of bamboo poles, each maybe 20 feet long—the South Asian equivalent of scaffolding—tied to a small cart in the road.

Even though today is technically yet another day of general strike, the steady hammering of manual construction echoes up and down the leafy street. A makeshift bamboo-and-blue-tarp café, the kind found all over south Asia, has been created against the wall of one of the villas, and half-a-dozen guys are standing or sitting around it, sipping tea amid a debris of tossed-out cans, cigarette cartons, paper and plastic. A cement mixer churns in front of the shell of a concrete building under construction; a boy descends a ladder from the cavernous second floor, a woven basket of sand on his head.

The entire scene has an air of slightly grim maintenance, of a step backwards driving each step forwards. The monsoon mud has been scraped into manageable heaps next to the deep guttering. Within the past 24 hours, one massive pothole at the intersection at the end of Road 12 has been loosely filled with what seems to be shattered pottery, which makes a crunkling sound when driven over. Another deep pothole, almost a sinkhole, has had a large tree branch thrust into it so vehicles won’t drive into it and emerge in, say, Cleveland.

All these apparently random observations on urban construction are not because I’m planning a late-in-life career change and qualifying as a civil engineer. They’re because of Blade Runner.

Back in the first of these Bangla blog entries, I wrote:

“As global warming melts the polar ice cap, that moisture has to go somewhere. Some of it causes the oceans to rise, or in our local case Lake Champlain, which set new records for flood levels and then refused to go back down. Much of it, though, falls as rain or hangs in the air as water vapor. Some say the world will end in fire, Robert Frost wrote, and some in ice. My hypothesis is that it will end in rain. It’s not the temperature that will be the end of us; as they say in Florida, it’s the humidity. Or to give this situation a more imaginable form, think of the landscape of Blade Runner: the world as one great collapsing city, under endless rain.”

I wanted to know whether Dhaka offered a glimpse into the future. Into the end of the world, in fact.

Sure enough, we’ve had humidity so thick you can virtually stand a spoon up in it. Sure enough, the city of Dhaka is not unlike the makeshift, wired-together, ancient-and-modern-used-parts Los Angeles of Blade Runner. And interestingly, both the fictional city and the real one speak a constant mélange of several languages in the same sentence, the most obvious sign of the globalization of culture, or at least of expression.

So why is it that Dhaka doesn’t have that depressing, dark, verge-of-collapse feel, that surly Philip K. Dick apocalypse?

Mainly, it’s that Ridley Scott’s view of the end of humankind is driven by the dystopian view that the end of the world will come because we caused it. We will get the future we deserve.

I don’t get that feeling in Bangladesh at all. Even though Bangladeshis themselves complain about their government, the pollution and the traffic, it’s clear that what’s going on here is not the self-inflicted decay of a once-great civilization. It’s the result of an ongoing 40-year struggle to survive.

Let me explain.

No country has ever had a more painful birth.

When East Pakistan pushed for independence from West Pakistan and the Awami League, a nationalistic party, won a majority in the 1971 national elections, West Pakistan sent in troops on a massive scale. One of the worst acts of genocide in modern times took place, with the Pakistani Army killing somewhere between 200,000 and 3,000,000 Bengalis. Mass graves have been discovered as recently as 1999.

When it became clear that a combination of Bengali and Indian troops were gaining the upper hand and that the Pakistani Army would have to withdraw, orders were sent down to cripple the infant nation by systematically killing its doctors, engineers, artists, writers and teachers, focusing in large part on students and faculty at Dhaka University. The archives suggest that the Pakistani army, with the assistance of local collaborators, systematically executed an estimated 991 teachers, 13 journalists, 49 physicians, 42 lawyers, and 16 writers, artists and engineers.

Another way in which Pakistan tried to kill the young country at birth was by torturing, raping and killing its women. Some 200,000 women were raped; the Pakistani Army captured young women from Dhaka University and middle-class homes and kept them as sex slaves in their barracks. It was the tactics of the armies of the disintegrating Yugoslavia, only 20 years earlier.

To say that the Bengalis who founded Bangla Desh (the land of Bengal) were forced to start from scratch, then, is like saying the Donner Party had a tough winter. It’s an amazing achievement the country isn’t still that pile of sand, that cart of bamboo.

The country is also extraordinarily vulnerable to natural disaster. The Bay of Bengal, narrowing and getting shallower as it approaches Bangladesh, concentrates wind and water to such effect that in 1991 a cyclone struck Chittagong at 150 m.p.h., driving a storm surge twenty feet high into a coastal area that at the driest of times is barely above sea level. More than 130,000 people were killed, some ten million were left homeless, and the resulting spread of water-born infections killed thousands more. The same scenario has been repeated depressingly often before and since.

The atmosphere in Dhaka, then, no matter how humid, is not one of caustic dystopia or fin-de-siecle ennui; it’s one of a people trying, literally, to keep their heads above water.

I say “literally,” because a new danger is emerging: of all the countries of the world, Bangladesh is most vulnerable to the effects of global warming—not only because a single-meter rise in ocean level will drive hundreds of thousands of people from their homes, throwing extra stress on the already overcrowded cities, the economy and the healthcare system, but because one of the features of global warming seems to be more extreme weather forms: storms like the 1991 cyclone may become the rule than the exception.*

This danger, more than any of the other difficulties facing Bangladesh, is the only one that might fall into that Blade Runner you-humans-will-get-what-you-deserve category. So any time you hear someone denying the validity of the science involved or insisting it be called “climate change” rather than “global warming,” tell them to spend a few weeks in Bangladesh. They’ll be picketing the governments and the major corporations before the month is out.

* I’m grateful to the research of Farhana Haque for information that forms the basis of this paragraph.

A Roundabout for Bangladesh

My final evening in Bangladesh started going downhill immediately after I’d done one of my favorite parting activities—overtipping the housekeepers. I had 3,000 Taka (roughly $40) or more, far more than was likely to need before the plane took off. So I gave them a tip that meant very little to me and a lot to them. Everyone was happy.

Almost at once, everything got worse. My driver arrived promptly at 6:30 p.m. and we saddled up, but the departure was affected by the fact that the garbage cart was parked outside. We’re talking an open handcart oozing raw garbage on a ninety-degree day, with magpies cawing and plucking at the ooziest of the fragments of organic waste.

Meanwhile, traffic seemed to be suffering from some illogical post-hartal sclerosis, and even little Road 12 was jammed. How a road can be jammed by only a dozen cars wasn’t clear to me, but in a mysterious eruption, no fewer than six small yellow trucks had parked across the road outside the wall of the Seabreeze International School (Cambridge Approved), as if some 12-year-old mastermind was planning a mass jailbreak.

As you can tell, I was still taking all this humorously, but once we’d made our way up Road 9, passing the Catalina Island Bistro for the last time, and forced our way onto the main road that runs from the Gulshan-1 roundabout to the Mohakhali flyover, it became clear that the traffic was disastrous even by Dhakan standards. That stretch of road, which had taken me perhaps 15 minutes to walk, and ran for maybe a kilometer, was solid. Took us 35 minutes to shunt our way through that kilometer, the road now full of vast shoebox buses held together with duct tape and Bondo, each one packed with people. At one point I saw a bus that so spectacularly violated the no-standing-in-front-of-this-line principle that the front of the bus, driver included, was six abreast. It was like teenagers in those bench-seat American cars of the Sixties and early Seventies.

I did my best not to worry about catching my plane, and instead stared at the tiny shops, trying to impress them on my memory. One was so chock-full of woven furniture it looked as though four day-release convicts had simply hurled the entire inventory out of the back of a lorry in through the front door. One sported a pile of jackfruit, easily the world’s ugliest fruit or vegetable: large, dirty-yellow and nubbled, jackfruit have a curious sagging quality as if the greengrocer has undergone a sudden fit of rage and beaten them up. Literally one shop if four was what in England would be called a “corner shop” or possibly a newsagent/tobacconist/confectioner. I wondered why, in defiance of my usual travel habit, had not bought a packet of biscuits to subsist on in my room, late at night. I realized it was because I knew those biscuits all too well: their colorful wrapping is unreasonably hard to open, and a single bite makes the biscuit explode in your mouth like sweet white dust.

Motorbikes and scooters and bicycles their way between the cars and buses; everyone else sat and honked. This traffic, I understood, was like four-dimensional Tetris. First imagine a version of Tetris in which seven columns of blocks descend from the top of the screen but there are only four docking columns at the bottom. Then imagine another set of blocks coming in from both sides. That’s what it was like, and the situation only got worse, rather than better, when people wanted to leave the playing area. Every time anyone wanted to turn right (remember Bangladeshis drive on the left) there was no light, no cop, no turn lane: instead, two or even three lanes built up over on the right, pushing their way into and across the oncoming traffic whenever the slightest opportunity presented itself.

My tolerance for the vagaries of Bangladesh’s infrastructure was fast wearing thin. Omar had promised me that when we reached the flyover and Airport Road, all would be plain sailing, and sure enough for about thirty seconds my driver actually used more than one gear. I felt like the joke about the snail sitting on the shell of the turtle, going, “Wheeeeeeee!”

But almost at once we ran into the right-turn problem again: the heavy rush-hour traffic had to essentially squeeze into the leftmost lane because at least two and perhaps three of the four lanes would be choked with people wanting to turn right across four lanes of rush-hour traffic. I found myself mentally pleading for just the tiniest expenditure in street infrastructure. If I had seen a roundabout, I think I would have cheered.

Because these roads violated the entire principle of segregation of purpose. Put simply, you want one kind of road to be high-speed limited-access, another kind of road to act as an urban highway with plenty of on and off opportunities but nothing to impede the flow, and yet another kind to move through commercial or residential districts where people are going to want to be stopping and starting all the time. Airport Road was a fatal collision of all three.

But the big surprise in urban infrastructural planning was still ahead. After countless right-turn squeezes, each one of which drained just a few more cars, motorbikes, mopeds, compressed-natural-gas auto-rickshaws, bikes and cattle from the traffic stream, we started to move more or less continually, and in the night-sky distance I saw the lights of a plane taking off from the airport. Then we stopped.

Complete stop. Utter stop. The kind of stop that feels as if no movement will ever be possible again. The zero degrees Kelvin of a stop. As far ahead as I could see, the traffic was not only stopped, it was being abandoned by its inmates, who were striking up conversations and probably starting roadside games of cricket.

What the heck was going on? After about ten minutes, a series of lights appeared among the vehicle taillights up ahead, apparently going sideways. Not only chemistry but physics and geometry had broken down. I started wondering when the next plane to Dubai would be, and the next plane from Dubai to New York, and the next plane from New York to my bed. Could planes even take off at Absolute Zero?

Finally I saw movement ahead, but once again it was movement in an unexpected direction: up.

Something was rising above the abandoned traffic. Then another something. They were rising in a pair of arcs…they seemed to be strangely striped….

Oh, my God. It was a railroad crossing. The main rail line to Dhaka ran right across the main road to Dhaka Airport.

My mind was still boggling at full speed by the time we pulled up on the Departures level, but I had no more time to devote to urban planning. It was now time to devote my attention to bribery.

The previous time I had flown out of Dhaka airport, I’d been dropped off amid roughly 71 million people jamming the curb, as if the entire adult male population of Bangladesh was about to embark on the Hajj pilgrimage. The press of bodies made an already sweaty situation sweatier, and I was about to dissolve into a pool of grease and lipids when a burly guy yanked me and my luggage from the line (more of a wedge, really), hauled me inside to the front of the queue, threw my bag into the metal-explosives-and-contraband detector and then demanded a large bribe. 71 million Bangladeshis, now behind me, glared balefully.

This time I wasn’t going to abuse my privileged position. I was going to stand in line with all the locals, sweat or no sweat. I had even stuffed a spare shirt into my backpack so after I had struggled into the airport proper I could change and fly in comfort.

My driver, who like all Bangladeshis had taken the ghastly drive pretty much in stride, dropped me off at a curb that was suspiciously empty. No Hajj pilgrims. No travelers of any kind. I handed my bag to the uniformed dude by the detector, which looked like a vast tubular vacuum cleaner, or possibly an iron lung. Dude sent the bag through. All done.

I stood for a moment, stunned by this unexpected success. What was I going to do with my spare shirt?

Interpreting my lack of movement as confusion, a uniformed second-dude asked me which airline I was flying. Emirates, I told him. He pulled a luggage cart from its nesting cluster, I put my backpack and travel guitar on it, and he walked me over to the Emirates line, fifteen feet away. The Emirates line, too, was surprisingly short and moving surprisingly quickly. I was pretty sure I hadn’t been in a shorter airport line since the last time I was in Urbana-Champaign, which has airport lines of one.

“Tip, sir?” The dude, having walked me the fifteen feet, broke into me pre-TSA nostalgic reverie and demanded compensation. I sighed. Well, at least he had done me a sort of a service, and that service hadn’t included jumping in front of 71 million pilgrims. I gave him 100 Taka.

He was not satisfied. “Two man, sir.” He gestured at a uniformed third-dude who had strolled over with us. “Two man.”

By now I was starting to see red—which is, of course, the color of blood in the water. Once again I had slipped from being a capable world traveler to a dumb tourist. Once again it became clear that the very vulnerability that makes travel a fascinating and even a spiritual experience also sets one up for being a victim.

I handed over the smallest bill I had left, checked in, and made for Immigration. A small group of uniformed Immigration dudes were going over people’s departure forms. I hadn’t yet filled one out. The nearest dude pulled out a blank form and asked me the questions. I gave him the answers, and he filled out the form. As I reached for it, he pulled it back slightly.

“Tip, sir?”

It was only his uniform that prevented me from assaulting him—a uniform, I realized, that meant nothing and that could be bought anywhere. I had only 500 Taka notes and dollar bills.

“I take American money, sir,” he said in tones that blended Uriah Heep and Ebenezer Scrooge.

By now, I couldn’t wait to get out. I went over to the bank counter to change my last 2,000 Taka. The clerk sneered at it.

“Is small amount, sir,” he sniffed. “Charge you 250 to change.”

At that apex of exhaustion and rage, I had a sudden moment of clarity. I knew exactly what I had to do about everything that had happened that evening. I had to snatch back my Taka bills from him. I had to run back to Immigration and grab my dollars from the fake immigration guy. I had to seize the baggage handlers and squeeze their throats until they gave me back my unwilling tips. I had to round up all that ill-spent money, add a little more of my own—which, now I saw things clearly, I was only too willing to donate—and I had to go back to Burlington, to my friend Dan Bradley in the Burlington Department of Public Works, and I had to buy Bangladesh a roundabout.

I wasn’t yet sure how big it would need to be, but Dan could advise me on that. Shipping would be a bit of an issue, of course, but by now I had friends with friends in high places in the Bangladeshi government who could probably slip it into the diplomatic pouch.

It’s only a small beginning, of course, but I know how to set up a non-profit, and the title alone—A Roundabout for Bangladesh—would guarantee news coverage, a worldwide response, phones ringing off the hook offering sympathy dollars.

I released my Taka and the bank employee surlily handed me a few dollars. But I was above all that now. I went to my gate, imagining cars, dented buses, bottle-green compressed-natural-gas auto-rickshaws, even cattle, all processing in an orderly, even stately fashion around Dhaka’s new roundabouts, wheels within wheels, the circulating machinery of a great city.

And the train—well, the train would need a tunnel, or a flyover. Now, that might be more of a challenge.

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post

Enjoyed your eyes and ears of B’desh

I am returning this week to Dhaka for a 3-yr stint , the “trailing spouse” of the new CFO of AIS-D. I hoPe to pull out the camera and pen for journeys into the teeming masses. Perhaps our paths will cross on some rain soaked, ricksha-infested, broken down, new street . Dekha Hobe! Marilyn aka Khunjoy

Leave A Reply