Of all the things I expected to do in Bangladesh (watching cricket, eating wonderfully spicy Bengali food, sweating through four shirts a day) something that didn’t make it on the list was being surrounded by Bangladeshi art. In fact, I hadn’t the slightest interest in or conception of Bangladeshi art. Well, I’m not alone: it turns out that Bangladeshis don’t know much (or, apparently, care much) about their own art, either.

Or so I was told last night during a wonderful, if slightly off-balance, evening at the home of the painter Fareha Zeba, her husband the sculptor Saidul Haque Juise and the eminent art historian Professor Enamul Haque, former director-general of the National Museum and Minister of Culture.

The evening was off-balance not because of the company, nor even because of the extraordinary range of original and collected artwork that turned every wall into a kind of concerto of visual activity. No, this was the evening before the notorious two-day general strike or hartal, which was busy throwing everything and everyone off balance even before it started. For one thing, the traffic, always…um…intense, was virtually at a standstill as some people tried to stock up ahead of the shop-closings, while others got ready to leave the city for what, with the Muslim weekend of Friday and Saturday and then two more days of hartal immediately afterwards, amounts to a six-day weekend. The strikers were adding to everyone’s nervousness by getting a kind of Cabbage Night jump on today’s strike by reportedly setting on fire eight buses, two private cars and a covered van, just to show they’re serious.

(I say “reportedly” because I saw no such thing, and having been in these situations before I know how vigorously rumor fans imaginary flames.)

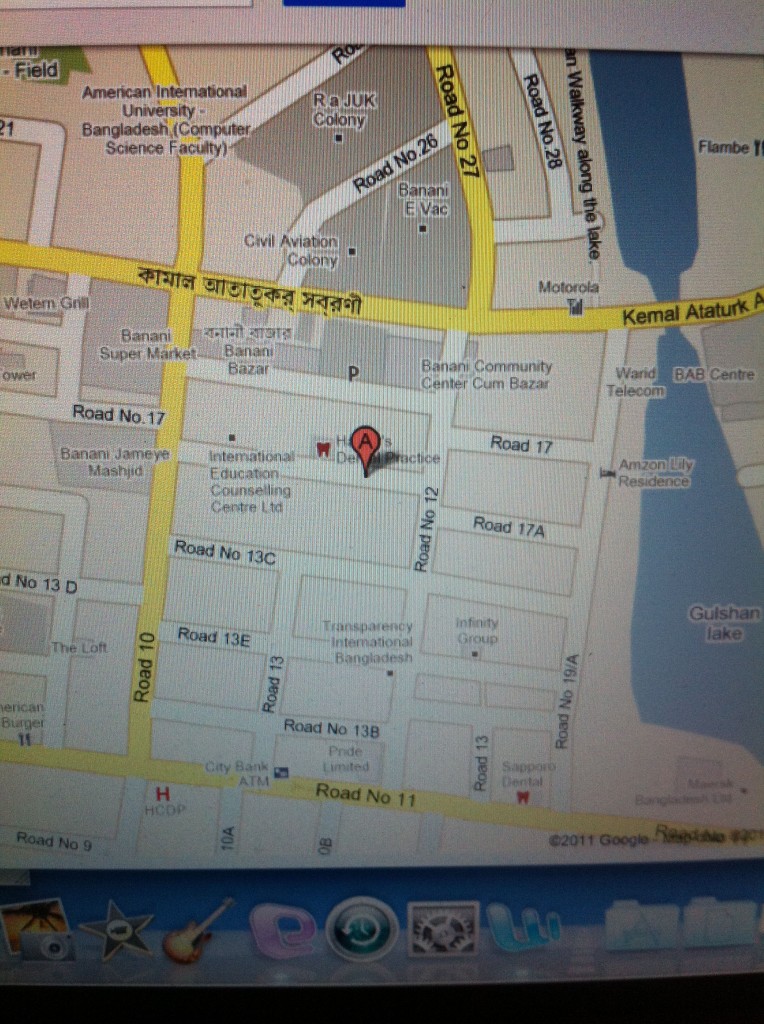

So a seven o’clock dinner was pushed back and back as everyone’s trips home were held up, and it was after nine before my friend’s driver turned up at the guest house where I’m staying. I hopped in, half-expecting the worst, but the rumors had done their job: Dhaka, which normally has more traffic on any given street in one day than the whole of Burlington, Vermont sees in a year, was almost deserted. The dark, leafy streets felt eerie, and for the first time I thought we might actually move fast enough that I’d need to put on my seat belt.

It hadn’t actually rained during the day (thanks to all of you who emailed me to ask if the weather was still as saturated as it was when I landed) but it was still humid enough that when I got out of the car my glasses fogged up with a tenacity beyond ordinary shirt-polishing, so I was standing like a fool with my specs in hand when the door opened and I was ushered into a home that I can convey only by embedding a dozen photos or more into what follows.

Fareha Zeba’s paintings, some in acrylics, some in watercolor, had a kind of sketchbook spontaneity to them and more than a hint of magical realism: it was as if the guests were surrounded by another set of guests, the spirits of Frida Kahlo and dozens of other long-lost friends.

These faces, though, were only the most conventional of those looking out from the walls and past the guests. Saidul Haque Juise makes masks. He started out making what might be called life-sized festival masks, crisp and colorful with a certain birdlike quality, but then he began using local sands, rust-colored and gray-green, creating a basic structure and then painting it with glue and paint before sprinkling the sand on top. The results were amazing, timeless and simultaneously somber and humorous.

And all the other walls were covered with all kinds of other pieces of folk art: more masks, more faces, birds, animals, gargoyles.

The whole wallscape left me feeling exhilarated but pretty stupid. How come I’d never seen or even heard of exhibitions of Bangladeshi art? Professor Enamul Haque cleared things up for me. Of course there is Bangladeshi art, from contemporary to seriously ancient, but Bangladeshis have spent most of their history pretty much ignoring it. Not a single college or university, he said, offers courses in Bangladeshi art.

This reminded me of a conversation I’d had with a very bright young tour guide in Egypt. Egyptians have no interest in their own history, he told me. I was flabbergasted. What country has a longer and more colorful history than Egypt, much of it still visible from miles away? No, he said, he wasn’t taught anything about Egyptian history in school; what little he knew what what he had picked up in his training as a tour guide. The reason why Egyptians in general are so well-disposed toward the English and the French, he said, was that it was the foreign archaeologists who not only unearthed Egypt’s art and history but declared it to be of value. Even today the vast majority of Egyptian art a visitor sees is either (a) 3,000 years old or (b) tourist crap. It’s like Egyptian food: I spent weeks in Egypt looking for good Egyptian food, but Egyptians who like to eat go out for French, or Italian, or Thai. It’s a kind of national self-diminishment I found quite dismaying.

Back in Bangladesh, meanwhile, a different dismaying trend has begun: Bangladeshi art has at last come to be valued–by smugglers. Even though in theory it’s illegal to traffic in, say, thousand-year-old stone icons, the trade is as lively as the African trade in ivory or rhinoceros horn. By far the top destination, he said, is the United States.

Even at his advanced age, Professor Haque has started a project that, he hopes, may help to slow this grim art-drain. Deciding that trying to enlist the help of politicians or academics was a waste of time, he chose a remote region in the north of the country a recruited–children. About 180 of them, in fact, all pledged to respect and preserve their country’s history and artistic heritage by reporting any trade they saw taking place in their immediate vicinity in icons, statues, sculptures, paintings, figurines. A kind of Neighborhood Art Watch.

It’s early days, but he believes his Baker Street Art Irregulars are having a significant effect. He hopes to set up similar projects in other areas of the country.

It’s early days, but he believes his Baker Street Art Irregulars are having a significant effect. He hopes to set up similar projects in other areas of the country.

And then it was time to leave, before the hartal proper got going at midnight. I said my goodbyes and headed back to the guest house, my mind full of faces.

At the risk of sounding relentlessly self-promoting, if you liked this piece you’ll almost certainly like my book Thirty Percent Chance of Enlightenment, available directly from me or from fine bookshops everywhere.