Well, you know how it goes. Just when you think it’s safe…..

So I had the Klonopin for just 24 hours, I’d had just one good night’s sleep and there I was thinking that things were on the mend. I was taking metoprolol, a beta-blocker, to keep my heart rate down, I felt more energy than I had in ten days, and I thought, well, let’s keep trying to extend my range, let’s just cycle quietly over to the park and stand in the goal for a little while to see what happens.

It was a beautiful day; after the amount of time I’d spent indoors, I felt almost blinded by the summer light, the open field, the lake and the mountains beyond.

When I say “soccer,” I mean a regular pickup game, players of both sexes, all ages, all abilities, from probably fifteen different countries. Played in a very good spirit, on not a very good surface, so what with having a couple of conscientious defenders in front of me and the fact that it was hard to string two passes together in a row, as a goalie I wasn’t exactly pushed to my limit.

Even so, something was clearly off. After no more than five minutes my heart felt full, a little heavy. After fifteen minutes I was getting a few petit mal symptoms—not a good sign. But they kept going away, so I kept going on. Maybe forty-five minutes in, though, everything kicked up a gear. Now my heart was racing, up to maybe 150 beats per minute. So much for the metopropolol.

I sat on the grassy bank behind my goal, trying to catch my breath. The attack kept feeling as if it was about to fade out, but then kept getting a second wind, then a third, then a fiftieth. I pushed my bike uphill to the main road, stopping every few yards, then cycled home along the flat. Oddly enough, I wasn’t afraid: after you play soccer, or any sport, for long enough, any injury becomes a good injury, a sign you were in the game.

By 9 p.m. it was still going on, though in a low-key way, perhaps thanks to the beta-blocker. My pulse at the base of my neck went 1, 1-2, 1, 1-2-3, 1, 1-2, 1.

I was almost fine when I was lying down, propped on my right shoulder (watching the original La Femme Nikita), but as soon as I moved, it all started up again.

So here’s the thing about information. Not only had I been discharged out into the world without a clear diagnosis, I also had no sense of what I should do about this attack, and nobody to ask. Sure, I could make another thousand-dollar trip to the emergency room, but by now I knew that if I went there one of two things would happen: (a) I could lie around like I was doing at home, except they wouldn’t have La Femme Nikita; or (b) they could shock me. I didn’t feel like option (b) unless I had a grand mal that went on for ten or twelve hours, so I decided to stay at home—but that meant I was left to my own ignorant devices.

Around 11 p.m. I did two things. I emailed my friend Dr Omar Khan, a co-conspirator in all kinds of adventures of mine and also a guy who seems to keep checking his email until 2 a.m. I also decided to take a Klonopin and see whether the soporific effect would also calm down my heart.

By 2:45 a.m. the Klonopin hadn’t really worked: I’d dozed a little, but was still palpitating, and now my Restless Legs Syndrome had literally kicked in. Well, my family doctor had said I could take up to 2 mg of Klonopin, so I took another. Next thing I knew, it was 7 a.m., and, clutching my chest like a man who things he may have left his wallet in the restaurant, I realized my rhythm had restored itself. I felt bathed in relief. Drenched. I crawled off the couch, staggered upstairs, fell into bed and slept until past noon.

The next couple of days were dedicated to not losing faith. I walked the dog, and every time she stopped to sniff I stretched as if I were planning to run a half-marathon that weekend. I did little half-mile bike rides to pick up small quantities of groceries.

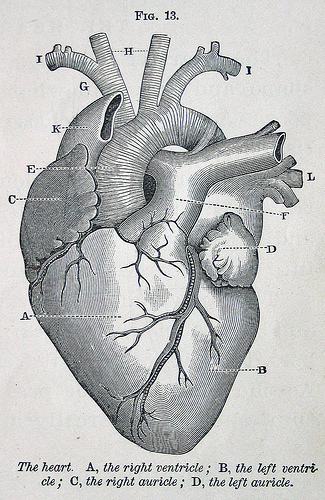

My cardiologist called to amplify what Jeremy, the EKG tech, had said about my beautiful heart. All four chambers, he said, are beating soundly with no evidence of thickening. There’s some slight leakage (he called it “regurgitation”) around my tricuspid valve and my mitral valve, but not nearly enough to cause (a) concern or (b) a. fib. Pretty much what we found last time, five years ago.

So the next step, he said, is to schedule a stress test, which would tell if I had any blocked arteries. If I didn’t, he said, then he could prescribe me anti-arrhythmia drugs, which sounded like a good idea but which apparently are under no circumstances to be used if there’s any heart damage. If I do have blocked arteries, I thought, then I guess they go in there with a balloon or a corkscrew. But I really didn’t think so. I really still put this all down to stress.

For the next week, nothing untoward happened. Each day I tried a little more activity. One day, as part of my resolution to see at least a little sunshine on every decent day this summer, I spent a couple of hours vigorously gardening, pulling impacted weeds, shoveling earth, bending and straightening over and over. No ill effects, a great sense of accomplishment. Another day I felt weird, and lay down for a serial nap that ended up lasting two hours. Determined again to see something of the glorious day, I cycled nearly a mile to Waterfront Video, the farthest I’ve ridden since the incidents began. It’s all pretty flat, but even so, on the way back I noticed things going awry. At first just the odd off-beat; then that pattern of an off-beat every seven or eight. I pulled over, having the sense that somehow the cycling was at fault. Standing or walking slowly seemed to make things no worse, at least.

After a minute or two’s rest I felt back on an even keel, and cycle on, trusting myself to go no higher than first gear. My heart fidgeted a little, but I got home okay.

On the way I realized something I’d never quite put into words before. The first erratic beat is alarming because it feels somehow larger than usual. Instead of being confined to its usual two dozen or so cubic inches, it seems suddenly to balloon up so I feel it throughout my chest, up in the base of my throat. There’s simply no ignoring it: something is wrong, something is struggling.

This general rhythmic uncertainty continued for much of the evening—not a flat-out madness but a low-grade loss of groove that meant that even getting up to move into the kitchen set me off that tentative regularity. And with it came a pallid, timorous emotional state that our friend Emily Skoler, who knows knows chronic illness and medical uncertainty better than most, calls “gray.” Lying down to try to sleep, my heart felt like a small bird in a cage knowing he’s being watched by a cat.

I had several email exchanges with Omar, who as usual was both informed and helpful. Except in one instance: because the ER docs had talked about the risk of blood clots rising appreciably if an episode of a. fib. lasts longer than 24 hours, I’d been pooh-poohing the notion of being put on blood-thinners for the rest of my life, as some a. fib. sufferers are. But when I happened to mention this to Omar over the phone, he said in a worried tone, “Oh, it only takes about two seconds for a blood clot to form.”

Another weird and unpleasant thing has started happening, possibly connected to the heart issues, possibly not: for two consecutive mornings, at around 6:50 a.m., I had terrible dreams in which things went wrong or broke down or fell apart and I was handed a bill for thousands of dollars—bills that, needless to say, I could no more afford to pay in my dreams than I can in conscious life. I woke up almost in tears.

Finally, on August 3rd I had the stress test.

Barbara drove me out to Dorset Street, a little over a mile from home, with my bike on the back of the car. She needed the car; I convinced myself I’d cycle back, as it’s pretty much all downhill. Part of me was saying “Um, this could turn out to be a terrible idea,” but I ignored myself.

The series of tests, which lasted nearly four hours, were pretty unspectacular. A nurse took a series of EKG’s, which were all normal, and notable only in that she managed to nick my chest with the razor and had to add a small circular plaster to all the electrode contacts she was sticking to my torso.

Next was an IV and some kind of isotope to help with a scanning series of images that took 17 minutes and during which I gratefully fell asleep.

Then came much waiting for Dr Fitzgerald, who was held up at the hospital—lots of cardiology needed on rounds this morning, apparently. Does the heart go wrong more often than any other major organ?

Finally he arrived, moved through his small gaggle of waiting patients, and came to find me (reading David Mitchell’s excellent novel Number9Dream) in the waiting room.

The stress test involved my walking on a treadmill that every three minutes raised itself to a steeper incline and accelerated. They wanted to see what happened to my heart when it got up around 140 beats per minute—and frankly, I was pretty curious too, especially as, if I did go into atrial fibrillation, I’d have to find another way to get home.

I needn’t have worried. Once again, as five years ago, my heart behaved like a trouper, and by the end I was up over 150 bpm, running uphill, and still it behaved itself. This was good news in more than one respect: it meant I don’t have a blocked artery, and that news in turn means I’m eligible for anti-arrhythmia meds. Maybe I’d need to take them for a month, maybe for ever. We’d have to wait and see.

But the two most interesting events happened after the stress test. First, once the treadmill was thrown into Slow Down mode, I had a series of little cooling-down spasms, right there for everyone to see, and damn peculiar they looked on the monitors. Yet after ten seconds or so the ship righted itself, and apart from a couple of brief PVC’s, all went back into Life On Earth mode. So once again it was the post-exertion phase that was the issue.

But surely the oddest part of the whole day was that I asked Fitzgerald for a copy of the read-out tape, which the nurse/tech insisted that he sign.

“It’s a medical record,” she explained to me.

“Oh, I thought he was signing it as a work of art,” I said.

I brought the printout home, cycling without the slightest problem, and later that evening I cycled over to Kinko’s and blew up one section of it by about 400%. I was going to carve it.

Initially, my thought was to give the carving to Fitzgerald as a present for him to mount on his wall, or his office door, or something, in which case he’d want a single complete healthy sinous beat, I expected. But then I thought it might look more interesting with two consecutive beats. When I got to Kinko’s and looked more closely at the printout, I realized I had a choice of all kinds of highly defective beats, as this section of tape was from my brief post-stress arrhythmia. For me, though, the bottom line showed the most promise: for about five inches it showed the frantic two-stroke beating of the high-speed arrhythmia, then it showed my heart restoring its native pulse and falling into that familiar peaks-and-valleys design probably used in cardiology ads everywhere.

Blowing up images on a Kinko’s copier is an inexact science, and what I ended up with was not exactly the final, healthy sequence I intended. It was, in fact, something much more interesting: it was the four transitional beats as my heart was getting back in the saddle, so to speak, and as such even a lay eye like mine could see the jagged tracing starting to smooth out and take on its graceful undulation.

This, I realized, was my signature—my cardiac signature. Probably everyone’s heart is slightly different, and beats slightly differently. This carving was a strange, even slightly morbid kind of self-portrait.

But it was also a story. Those four measures, to think in musical terms, tell the story of that mysterious electrical force buried deep in the tissues of my heart and its successful struggle to overcome whatever agency of chaos and old night had temporarily thrown it for a loop—or, to be more exact, a series of croquet hoops. This was the story of strength renewed and hope restored. It was, in effect, the Human Comedy—the journey undertaken by the naïve everyman into parts unfamiliar and unknown, the journey that ends with everything returning to normal. And for the cardiologist, a job well done.

I really love the stormy ripple and curl in the maple behind/underneath the EKG line. The standard medium is, of course, graph paper, which makes sense of you want to quantify the event. But artistically that implies that the EKG line exists within the possibility of a Platonic or Euclidean perfection: the grid gives our heart something to match up to, or against.

And the truth is, it can’t. Hearts can be healthy but they can’t be perfect, and they can’t all achieve the same peaks and valleys that imply ideal functioning. We each have our cardiac quirks and idiosyncrasies, just as we each have our own array of freckles, of bruises and small scars, of the archaeology of major surgeries.

The stormy background of the maple wood suggests that this line is only one of many, many rhythms and dynamics that make up our lives, and our lives within the world as a whole. All I’ve done, as an artist, is pull out one of those rhythms, those currents, those threads of constant and complex change.