Of course, I was hoping that my visit to the cardiologist the day after next would not only answer my questions (Why had this all started up again? What was causing the individual attacks? Why had the one on Monday night seemed so different to the one two days later? Would I have to keep getting shocked? Would I have to have a pacemaker? Would I have to have that terrifying-sounding operation in which the surgeon burns away part of the heart?) but even go so far as to tell me that nothing had really happened, and that I would play soccer until I was a thousand.

Of course, nothing of the kind happened. Total number of questions answered definitively: zero.

The cardiologist, Dr John Fitzgerald, took a good listen to my heart and his tech stuck more of the EKG electrodes on my formerly hairy chest, which was now starting to resemble the patchy hide of an extremely unhealthy donkey. At that particular moment, my heart was beating away with a quiet confidence I personally didn’t share. This, I realized, was the problem with having an intermittent condition (like asthma, or headaches, or a weird noise emitting from the transmission at any time exceptwhen the car was in the shop: they couldn’t tell me much until things started going wrong again.

Fitzgerald ordered a more comprehensive EKG accompanied by an ultrasound. In return, I asked him about ablation: was it really as routine as Weimersheimer had made it sound? (After all, cardioversion was simultaneously as routine as he had made it sound and yet really, really not.) I imagined the chest being opened, a stainless-steel or chrome spreader opening the ribs, and the surgeon leaning over me holding something that looked suspiciously like a soldering iron.

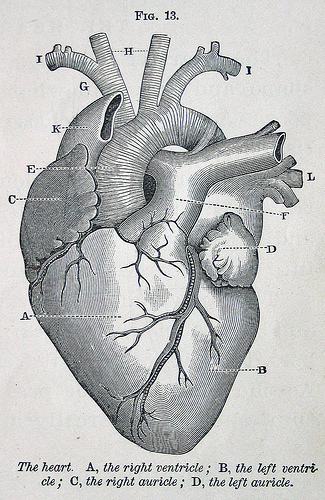

But no: the surgeons go in through the thigh, Fitzgerald explained, pushing thin, flexible wires up through major blood canals until they reached various key points of the heart. (I was inwardly boggling, imagining someone in scrubs pushing a piece of well-cooked spaghetti in through my thigh while squinting intently at a map of my vascular system that looked like a more complicated diagram of the London Underground.) Having miraculously persuaded these wires to these critical points, the surgical team (also called electrocardiologists or electrophysiologists) can first take readings to plot the electrical circuitry of the heart, and then send a high-frequency radio signal to burn out a particular nest of nerves that was misfiring, burning it to scar tissue. So many parts of this procedure defied belief I couldn’t bring myself to think about it.

In the meantime, I was facing the even less answerable question of how to live my life while waiting for all the big cardiology questions to be answered–and on this issue, nobody in the medical profession had been able to give me any advice that was any more fine-tuned than Weimersheimer’s cheerful reassurance that if things went wrong again, I could always come back to the ER and they could shock me back into shape.

How much activity could I do? Was a certain amount of exercise a good thing? I had an appointment to meet a student across town and cycled there, all downhill, and though nothing untoward happened, my heart felt as if it was laboring. On the way back I pushed my bike up the uphill stretches and rode it only on the (mainly) flat, but even so by the time I got home it was skipping and hopping every few beats, though it settled itself down, thank God. I named this kind of event (borrowing epilepsy terminology) a petit mal, or minor event: something was wrong, but it wasn’t disabling and it seemed self-correcting. The attacks I’d had on Monday and Wednesday nights were the grand mal, the real deal.

If I had to come up with one defining difference between the two, it would be the racing heart. I’ve now heard from at least a couple dozen people who suffer from a. fib., and it has astonished me how many of them have put up with it for weeks, months or even years. Yet if I think of the petit mal and imagine that low-level skipping and jumping, I can imagine not noticing it. A couple times recently, even in my ultra-heightened state of awareness, I’ve not been sure if I’m on pulse or not. But the grand mal, the heart beating at 150 or even 180 times a minute, threatening to burst up through your throat–some of the a. fib. sufferers I’ve been corresponding with or talking to have never had that.

The ultrasound, which was set up for Saturday morning, was something I’d had before (see A Barrel of Monkeys) and had found utterly fascinating. Once again the tech (whose name was Jeremy) had me lie down, then wired my threadbare chest to his computer, made with the gel and began moving his wand around to see the ghostly sketch of my working heart from various angles.

By inclination and training he was an artist; his day job simply involved making pictures for doctors. As we talked, he moved the ultrasound wand a little like a joystick, his eyes on the screen, and when he got exactly the angle and the image he wanted, he took the mouse with his other hand and plotted a number of salient points on the screen, converting the pulsing sketch to data.

“You have a beautiful heart,” he said, examining his monitor closely.

Under the circumstances, this was both a compliment and a relief, and I told him so.

He’s seen all kinds of hearts, he said, many of which were not beautiful.

Genetic issues, I asked, or damage?

Damage, he said. Oddly enough, congenital defects, which normally seem both ugly and frightening, are rarely the worst of our troubles. It’s amazing how our bodies adapt, he said. No, the main problems are all self-inflicted: smoking, bad diet, bad lifestyle.

Every so often he punched a key that made the computer broadcast the sound the heart was making, or perhaps more accurately a digital facsimile of the sound. I was struck by how it sounded almost like a chuckle: cheerful, optimistic, just going on with its business.

To some people, he said, it sounds like a washing machine, turning the water and the laundry in the drum back and forth, back and forth. “You should hear the mitral valve,” he said. “We’ll get to it in a minute. People say it sounds like a dog barking.” But to me it sounded like a deejay rubbing the vinyl on the turntable with his fingertips, wacka-wacka, wacka-wacka.

I told him how stunned I’d been by the mitral valve, when I had first seen it on the ultrasound.

Yeah, he agreed. We think we invented plumbing and electricity, but it’s all there in the heart, in far greater complexity than we can even fathom.

Imagine an engineer being asked to design something as supple and perfectly-fitting as the mitral valve, I suggested, and then saying, “Oh, yes–and make it work perfectly, without stopping, for 85 years.”

Jeremy nodded. “We’ve tried, and we *know* we can’t do that.”

I left with yet more mixed messages. No heart murmur, no valve leakage, no signs of heart disease–but, at the same time, no understanding of what was causing my condition, what might help it, and how the heck I should live my life until we found some of those answers.

As you can probably gather, this is by no means the end of the story. I hope you’ll follow as I add new chapters every few days and continue to explore both the narrow subject–atrial fibrillation–and the broader subjects, such as the heart itself, and what Whitman called “the body electric.”

I also hope you’ll forward this to anyone who has arrhythmia. This may possibly turn into a book, in which case I need all the help I can get from others, whether what they have to offer is answers or questions.

Back soon.